RECENT COMMENTS

The Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District

Anchored by Chimborazo Park and Oakwood Cemetery, the Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District was shaped by the events of the 20th century, from the development of the trolley to the racial transition of the community during the 1950s and 1960s.

The Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District

- Map of the Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District

- Early National and the Antebellum Periods (1789 –1860)

- Civil War (1861-1865)

- Reconstruction and Growth (1865-1917)

- World War I to World War II (1917-1945)

- World War II to the Present (1945 – 2003)

- Credit and Sources

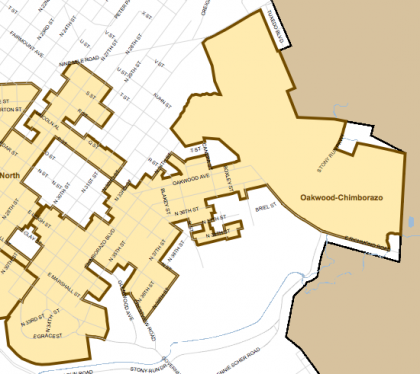

Map of the Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District

The Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District encompasses Chimborazo Park and Oakwood Cemetery, and the corridor between the two. The district abuts the St.John’s Historic District to the southwest, and the Church Hill North Historic District more directly west.

Early National and the Antebellum Periods (1789 –1860)

As with much of the eastern portion of the City of Richmond, a discussion of the early history of the Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District must begin with Col. Richard Adams and his heirs. Around 1769, Adams began purchasing enormous tracts of land to the north and east of Church Hill in anticipation that the city would grow to the east. The 1789 decision to move the capitol from Williamsburg to Richmond only strengthened Adams’ conviction that the city would expand in an easterly direction. In anticipation of this growth, Adams laid out his vast holdings in the same grid pattern as the rest of the city. Adams also offered then-Governor Thomas Jefferson his choice of prime building sites for the new capitol building. Ultimately, Shockoe Hill was chosen as the site for the capitol and Adams’ vision of the easterly expansion of the city was dashed. Richard Adams died in 1800 and left the majority of his estate to his eldest son and namesake, Richard Adams II. Richard Adams II died in 1817 leaving no children. By his will his executors were directed to divide his vast estate, with an estimated worth of $1,200,000 in 1821, between his nieces and nephews. A plat for the division of Richard Adams’ land shows that it encompassed much of the current historic district from Broad Street north to R Street and from 30th to 34th streets. Thomas Rutherfoord owned large tracts of land to the south, west and north and Christopher Walthall, James Malone and Samuel Pleasants owned large tracts east of 34 Street. With the exception of the Spring Garden tract, which Richard Adams I sold to George Winston prior to 1787, very little of the area was developed before 1835 when his heirs began to sell off larger tracts. The greater Church Hill area began its measured growth only towards the end of the 19 century as land was subdivided into building lots or resold as investment property.”

In the thirty years following Richmond’s selection as the state capitol, its population nearly tripled from 3,761 in 1790 to 12,067 in 1820.9 The growth in population created a demand for burial space. Most of Richmond’s early citizens were buried either in privately owned cemeteries or in church graveyards. But by the early nineteenth century, these places were filling up creating the need for a municipal cemetery. In 1820, the City acquired four acres on Shockoe Hill for the city’s first municipal cemetery. Hollywood, a 42-acre private cemetery was established in 1847. By the 1850s, it was necessary for the city to purchase and develop another cemetery. To this end, 66 acres in Henrico County were purchased from Fendall Griffin and the heirs of William Cook. Additional land has been acquired and today Oakwood contains 175 acres. The first burial took place in 1856.

Civil War (1861-1865)

The war came quickly to Richmond. In December 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union, followed very quickly by five other states. During February of 1861, a new government was formed and Jefferson Davis was elected provisional president. On 12 April 1861, South Carolina fired on federal troops at Fort Sumter and three days later President Lincoln called out 75,000 volunteers to quell the insurrection in the south. Virginia voted to secede from the Union on 16 April 1861 and on 22 April Robert E. Lee accepted the post of major general commanding the Virginia forces. Daily, young men began arriving in Richmond from all over the south to train under General Lee. Army depots were established at several places throughout the area including Chimborazo Hill. On 29 May 1861, Jefferson Davis arrived in Richmond, the new confederate capital. In June 1861, the task of building the defenses around Richmond began. “Street cleaners were put to work building the fortifications and unemployed free Negroes were seized off the streets for similar tasks.”10 There were three lines of defense around the city. The inner line consisted of “star forts”, as many as twenty-five by 1864, that extended around the city from the James River on the east to the James on the west. The river was the southern boundary of the city in 1861. These forts were constantly occupied by a detachment of ten or more soldiers. An intermediate line of earthworks encompassed the city in a five-mile radius from the capital building and the outer line was set at a seven to nine mile radius. Star Fort number four or Confederate Gun Battery Fourteen, part of the inner defenses, was located in the district near the intersection of P, North 35th and the East Richmond Road.

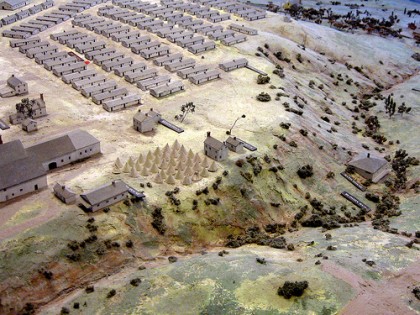

Originally intended to serve as winter quarters it was determined that Chimborazo Hill was better suited for a hospital, given there were already two or three hundred sick soldiers quartered there.11 When the Confederate army took possession of the hill it was separated from Church Hill by Bloody Run. A bridge needed to be constructed and the Broad Street extended to link the hospital in Henrico County with the city. The forty-acre complex was organized around five hospitals, one for each state represented—Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, and Georgia, and each hospital had thirty wards. The wards were one-story board-and-batten buildings that measured 100′ by 20′ and were furnished with two rows of beds and a center aisle. In addition to the wards and hospital buildings, there were 100 Sibley tents, five soup-houses, a bakery, a brewery, and five icehouses. Seven thousand to 10,000 loaves of bread were baked daily, and up to 400 kegs of beer brewed. Caves or vaults were dug at the eastern end of the hill to keep the beer. The hospital leased nearby Tree Hill farm for the pasturage of 100 to 200 cows and 300 to 500 goats. There were also gardens to provide fresh produce for the patients.12 During its existence more than 76,000 sick and wounded Confederate soldiers were treated at Chimborazo. Chimborazo was one of the finest hospitals the south and possessed a mortality rate of less than twenty percent. The utilization of a ward system and the large-scale use of women as matrons and ward attendants were medical innovations pioneered at Chimborazo. The memoirs of Phoebe Yates Pember, a matron of one division of Chimborazo Hospital, document her experience there from 1862 to 1865 and describe conditions in a major Confederate hospital.

To the north of the hospital was Oakwood Cemetery. As the war began to take an increasing toll, the Council of the City of Richmond authorized the Committee on Oakwood Cemetery to designate a place for the burial of Confederate soldiers who died in Richmond or Henrico County. The committee offered the Secretary of War as much acreage as might be necessary to bury the dead. On 13 January 1862, John Redford, the Keeper of Oakwood Cemetery reported that up to 31 December 1861, “eight white females, five white males, two females of color, and twelve male Negroes had been buried in Oakwood Cemetery. He also stated that up to January 12, 1862, 540 Confederate soldiers had been interred.”13 Mr. Redford reported to Council on 8 September 1862 that in the preceding year 4,882 soldiers had been buried at Oakwood and by January 1863 the total had risen to 7,120.14 The final count rose to 17,200 after the war as soldiers were reinterred from the battlefields around Richmond. Union soldiers, black and white that died in city prisons or hospitals were also buried at Oakwood Cemetery. Cemetery custodians struggled with the effort to provide maintenance for the large number of graves.

Reconstruction and Growth (1865-1917)

Twenty-eighth Street was the farthest street to the east that linked Broad Street and Nine Mile Road. Broad Street was interrupted just east of 28th Street because of the ravine at Bloody Run Creek. Twenty-ninth and 30th streets stopped at Marshall Street and 31st Street terminated at Clay Street.

Thirty-second and 33rd street ran for two blocks between N and P streets and the East Richmond Road headed diagonally to the northeast from the intersection of P and 33rd streets. There still existed a few large estates and sparsely scattered dwellings and homesteads. The Oakwood- Chimborazo area lay outside of the City of Richmond until 1867 when the land west of North 31st Street, south of Marshall Street and east of North 35th Street was annexed. The bulk of the district was still a part of Henrico County until 1906 when the City of Richmond annexed the area to the east and north.

On 13 April 1866, the federal government adopted a resolution creating national cemeteries and made provisions that the Union dead would be removed from battlefields and other cemeteries to be reinterred in these new cemeteries. The remains of nearly 5,700 Union soldiers were reinterred at the new National Cemetery on Williamsburg Road. In response to the resolution which excluded the Confederate dead, a group of 100 women met and formed the Ladies Memorial Association for the Confederate Dead in Oakwood Cemetery to provide care for the graves of the veterans buried there and adopted 10 May as an annual memorial day. “On Thursday, May 10, most city businesses closed in honor of the day; the first recorded Memorial Day in Richmond. At 10:00 A.M. a brief service was held at St. John’s Church, then the crowds walked to the Confederate section at Oakwood Cemetery. After the speeches ended, the audience placed flowers on the graves and assisted with the ongoing effort to clean up the cemetery. A similar celebration was held at Hollywood Cemetery at the end of May and other memorial associations throughout the Virginia and the South held comparable observances. It is generally assumed that Confederate Memorial Day celebrations were the inspiration for today’s national Memorial Day.

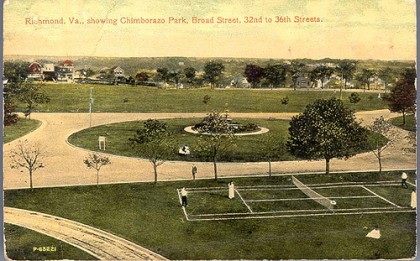

Within weeks of the surrender at Appomattox, Chimborazo Hospital and its buildings were turned over to the Freedmen’s Bureau to provide temporary shelter for Black families in the city. By 1866, the hill had become a permanent black settlement complete with a church. Also in 1866, F. Frommel had acquired the use of the vaults at the eastern end of Chimborazo Hill and was operating a brewery there. Joseph Bacher acquired seven acres at Chimborazo including the vaults around 1870. Bacher, the third brewer to try to operate a successful brewery on the hill met with failure quickly. The vaults proved to be too warm to keep beer at the desired temperature and ice was too costly and scarce. Bacher went bankrupt, sold his seven acres to the city and returned to New England. In 1874, the City of Richmond began acquiring property for a park in the eastern part of the city that included the old hospital site.

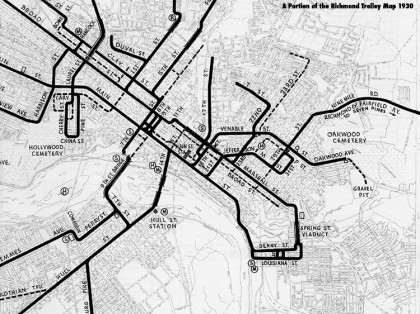

By 1896, the Richmond Traction Company was operating two trolley lines in the area. One line ran along Venable Street to Q Street then out Oakwood Avenue to the cemetery. The trolley continued east beyond the cemetery to the gravel pits south of East Richmond Road near Gillies Creek. A trolley barn was located on the eastern side of Oakwood Avenue near the entrance to the cemetery. A second line operated along Broad Street from the reservoir on the west to Chimborazo Park on the east. The Richmond Railway and Electric Company operated a loop through the neighborhood that traveled from Broad and 29th streets north to P Street then west to 25th Street where it turned south to Jefferson Avenue. The track followed Jefferson Avenue to 21st Street where it turned south back to Broad.

Commercial development began to appear in the neighborhood. Around 1900, Hiram H. Herbert opened a confectioner shop at 401 Chimborazo Boulevard. Grocery stores followed at 520 North 31st Street, 500 North 33rd Street, and 3120, 3301, and 3306 East Marshall Street. Morgan B. Wilhelm operated a General Merchandise store at 3307 East Marshall Street in 1915 and Richardson’s Drugstore opened at 501 North 31st Street in 1909. As late as 1889 land was still held in large tracts by families such as Cowardin, Canepa, Brill, Schaaf and Brauer. The property east of Oakwood Avenue was laid out first by East Virginia Land and Improvement Company. They also owned land around 37th and 38th Streets but developed separately in 1915 as the Vineyard Tract, “taking its name from the vineyard operated there by Dr. J. B. McCarty around 1877.” The land west of Oakwood Avenue was surveyed and subdivided around 1908.

A black middle class had begun to coalesce in the 1840s. Church societies and associations were at the heart of the process by which people, both free blacks and slaves, defined themselves, especially in the emerging black middle class. Congregations served as mini governments and enforced the rules of evangelicalism, temperance and benevolence. “In Richmond, evangelical religion and benevolence, marriage and a paternalistic household, steady wages or profits, and education were the characteristics of a black middle class that appeared after Emancipation but began its formation years earlier.” The black middle class was composed of teachers, lawyers, businessmen and ministers but more importantly it was dependent upon black professional and laboring women.

The arrival of the black middle class is no better illustrated than by the founding of Evergreen Cemetery in 1891 and the people buried there. The goal was to develop a cemetery that would rival Hollywood Cemetery, the elite resting-place for Richmond’s most influential white citizens. Evergreen was to be a “memorial park fit for royalty.” The cemetery was the most prestigious place in Richmond where an African-American could be laid to rest. It proved so attractive that bodies were removed from older, less distinguished cemeteries and reinterred at Evergreen. A four-foot angel stands atop the grave of Rebecca Mitchell, near the grave of her son, John R. Mitchell, Jr.

John Mitchell was born 11 July 1863 of slave parents. He was educated in church schools and at the Richmond High and Normal School. He taught school for three years and served on Richmond City Council from 1888 to 1896. In 1921, he ran for governor. In 1884, “he took over as editor of the Richmond Planet, a weekly newspaper for blacks. The Planet grew to be one of the country’s leading black newspapers.” It was from his desk at the Planet that Mitchell fought tirelessly against injustice. He was also founder and President of the Mechanics Savings Bank and was the only black member of the American Bankers Association. Mitchell died 3 December 1929 and was buried at Evergreen.

Across the lane from Mitchell’s grave is the grave of Maggie Lena Walker marked by a large cross. The graves of several other family members surround Walker’s. Walker was born on 15 July 1867. Her mother was a former slave and her father, a white abolitionist. Like Mitchell she attended the Richmond High and Normal School and taught school for three years. She attended business school and later received a Master’s degree in business administration from Virginia Union University. In 1886, she married Armistead Walker. In 1897, she began a long leadership role with the Independent Order of St. Luke, a fraternal business organization. In 1903, she founded and became the president of the St. Luke’s Penny Savings Bank, making Mrs. Mitchell one of the first women to become the president of a chartered bank. In addition to her achievements in business, Maggie Walker was also known for her unselfish community service. Maggie Walker died 15 December 1934. Her house in Jackson Ward is a National Historic Landmark.

Not far from the graves of Mitchell and Walker is the grave of Rev. John Andrew Bowler. Rev. Bowler was one of Richmond’s foremost leaders in the field of education. He began teaching at the elementary school level in 1882 and later organized the George Mason School. He served in the educational field for over fifty years. Around 1900, he became an ordained minister and was the founding pastor of Mt. Olivet Baptist Church. Evergreen is also the final resting-place African-American veterans of the Spanish-American War and World War I and “Buffalo” soldiers who served in the U.S. Cavalry following the Civil War. There are over 5,000 graves at Evergreen.

World War I to World War II (1917-1945)

The Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District experienced another sustained period of growth from 1923 to 1926 as families like the Cowardins, Pleasants and Andersons began to subdivide and sell off their holdings. Edwin Pleasants lay out and subdivided his family estate known as Pleasants Woods in 1924. Three years later, Lynbrook Realty Corporation platted the same property as Glenwood Park. The property west of 34th (named Chimborazo Boulevard in 1910) was platted before 1876 but the land east of 34th was not subdivided until after the turn of the century.

The Cowardins owned the land fronting Chimborazo Park that was gradually subdivided. Large townhouses were built on the resulting lots one at a time over a period of roughly forty-years. The M. G. Billup House constructed in 1931 was one of the last houses built on Broad Street east of 34th Street. The Cowardins and Pleasants also held the land north of Clay into the 20th century and did not develop it until the 1920s.

Prior to 1930, the trolley line was removed from Broad Street and relocated to Marshall Street. This encouraged commercial development in the Marshall Street corridor. By 1944, buses were operating on Broad Street to 34th Street where they turned north. By 1949 the trolleys were gone. Unlike many other neighborhoods of this era, the development of the Oakwood and Chimborazo neighborhoods was not dependent upon the trolley lines like the new suburbs being created to the north and west.

World War II to the Present (1945 – 2003)

Little development has taken place in the Oakwood-Chimborazo historic district in the years following World War II but significant changes have taken place. Houses were constructed in the 600 block of North 39th Street in 1946, completing the Glenwood Park development. The next wave of construction came in the 1960s when houses were constructed along the eastern edge of the district by and for the areas growing African American population.

A comparison of census figures for the years 1940, 1950 and 1960 illustrate the racial transition of the neighborhood. In 1940, there were 6,885 white and 2,124 African Americans residents. The change in total population and racial composition between 1940 and 1950 was imperceptible. But the ten years between 1950 and 1960 saw a transformation in the community. By 1960, the white population in the neighborhood had dropped to 391 and the African American population had grown to 9,203. What is interesting is that the percentage of renter occupied housing units declined indicating that many of the new inhabitants in the area were owner occupants. This trend is contrary to the typical increase of absentee ownership and renter occupied housing normally observed in the transition of city neighborhoods.

“The east end area of Church Hill had grown up earlier adjacent to a major commercial and industrial district and housed the city’s burgeoning white working-class… Clearly, though, Richmond after 1900 came to be less ‘a jumble of rich and poor, immigrant and native, black and white’ and approached more nearly what Sam Bass Warner, Jr. referred to as the ‘segregated city’… The impact of streetcar suburban development was the segregation and isolation of the city’s older neighborhoods… The gradual exodus of the middle and upper classes to the suburbs enhanced fragmentation.”

The transition of the neighborhood is clearly illustrated in the changing school populations. Chimborazo School opened in September 1905 with 377 white students. In 1911, an annex with additional classrooms and an auditorium were opened. In 1958, the remaining 280 white pupils were transferred to Nathaniel Bacon and Chimborazo school converted to a black school. The new Chimborazo school opened in 1968 and the old building was used as the Church Hill Opportunity Center and an annex of East End Middle School. The building was surplused in 1973 and privately rehabilitated as housing for the elderly in the 1980s. Nathaniel Bacon School opened in September 1915 with 380 white pupils, and closed in September 1958 and the pupils were transferred to East End Middle school. The school was reopened in October 1958 with 351 Negro students from Chimborazo and George Mason schools. A ten-classroom addition was built in 1960 and between 1970 and 1982 the building served as an annex to the East End Middle School. Nathaniel Bacon closed June 1988 and was declared surplus property on 4 October 1988, converted to elderly housing. East End Junior High School opened in September 1929 with 1,021 white students transferred from Bellevue Junior High School. In October 1958, the elementary grades were transferred from Nathaniel Bacon and the school closed June 1959. All of the pupils were transferred to Robert Fulton, Highland Park, Chandler and John Marshall schools. The school reopened in September 1959, as black Junior High, with grades seven to eight and 252 students. The building was damaged by a fire in 1964, was repaired and continued to operate until June 1991 when its programs merged with Mosby Middle School. In 1992, the building was renovated for use as a school and reopened as Onslow Minnis Middle School.

Credit and Sources

The text above is almost entirely sourced from the the registration form from the Oakwood-Chimborazo application to the National Register of Historic Places (PDF), with introductory text based on information in the National Park Service’s Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District. The original document, dated September 2003, was put together by Kim Chen and includes much more more than is shown here. Check out the original form to learn more about the Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District, or read up on any of the other sites in Richmond that are listed on the National Register.

The map at the top is a detail from the city’s Richmond Districts and Sites on the National Register (PDF). The photo of East End Junior High is by Will Weaver. The two trolley images are from Carlton McKenney’s Rails in Richmond. The source of the Chimborazo Park postcard is unknown. The 2 black & white photos are from the Oakwood-Chimborazo registration form. All other photos are by John Murden.

John- WOW! Great job pulling all of this together. It makes for great reading…

All I did was copy&paste and clean that up a little, the real work was done in getting the application together.

Well done, John. Thanks for putting this together in one place.

Why couldn’t the districts have been separate? They’re two separate neighborhoods.

Thanks John!

Cadeho, #4 – that question would be best posed to Kim Chen, since she put the application together. I don’t think she posts here on the blog, don’t recall seeing anything she’s posted in the past (though I could be wrong) so if I remember it and happen to see her or remember to call her, I will suggest that she answer that question by posting here.

John Murden, I think you’ve done a wonderful job of pulling this together and adding pictures that really make it come alive. Reading a national register nomination can be kind of dull, even when it’s interesting, but it’s really lively here on the blog, thanks!

GREAT article, even if you did just copy and paste stuff – it’s good to have it all here in one place. Thanks for using my photo. 🙂

“The impact of streetcar suburban development was the segregation and isolation of the city’s older neighborhoods… The gradual exodus of the middle and upper classes to the suburbs enhanced fragmentation.”

What would a streetcar system do now? Would it lead to greater flight, or would it help convince suburbanites to rebuild their nests in the city? Would it allow local business owners the chance to build local success stories? Would it encourage tourism (without making parking an issue)?

If money weren’t the priority (because unfortunately in this town, it always seems to be), what would a return of the trolleys do for Church Hill?

The trolley map is dated 1930. If you really want to bring something from the past into thinking about Church Hill’s future; imagine what Church Hill would be like in 2030 (essentially one generation from now). What do you see?

I see a prosperous community that would be larger than most, but vibrant, diverse, and full of potential. Maybe if it got denser, not only in population, but also in business and culture, the Church Hill district could sustain being separated into different districts.

Right now, the 7th district needs to work together to make it all it should be – A diverse, regional nexus point for the city, on the order of Carytown (just imagine changing that proposed line on 23rd St to 25th St). 25th and Q could become a local business hotspot, and if fiber optics were added when the tracks were dug, we’d also have the beginning of high speed internet for the greater Church Hill community, which would do wonders.

Just a thought. What’s everyone else’s?

I need to do some research.. I really want to know what Richard Adams didn’t own because he seemd to have had a huge bulk of the east end. I’m surprised there’s nothing named after him… Union Hill I believe had a street named after him or his family but was renamed when annexed because of the other Adams St.

Mr. Adams bought up a considerable portion of the East and Church Hill area when he thought there was a chance that the Capitol was going to be placed on Church Hill. He and Jefferson argued about its location and Jefferson put it where it is sited now on Capitol Hill and not on Church Hill. This caused a personal and professional riff between to two very powerful Richmonders and they never spoke again before they both died. After the Capitol was decided not to be on CH, Mr. Adams then began selling off some of this land but not at near the profit he would a realized, if the Capitol were to be sitting (let’s just say), at the corner of 25th and E. Broad St.

In the part about Chimborazo, they say “Caves or vaults were dug at the eastern end of the hill to keep the beer.”

let’s go look 🙂

The name refers to the two major landmarks located at the ends of the district — Chimborazo Park and Oakwood Cemetery. Historically, the area was not developed as two distinct neighborhoods but rather in a series of speculative developments as larger family-held properties were subdivided. The smaller developments blended together over the years. Today we tend to split the area into two neighborhoods based on proximity to the park and the cemetery.

Wonderful summary of a wonderful neighborhood. My grandparents met and courted in Chimborazo Park in 1924.