RECENT COMMENTS

Public housing in Richmond

RRHA’s public housing communities provide housing for more than 10,000 people in 11 family public housing developments and eight elderly housing buildings throughout the city.

The move for development of public housing in Richmond began in the early 1930s as a push by the Public Works Administration (PWA) for a project to be built just north of Virginia Union. This development derailed when residents pushed back against the location. Then in 1935 PWA proposed slum clearance, the demolition of blocks of substandard housing in Jackson Ward, coupled with the construction of hundreds of units of low income housing.

Proponents of the plan said that residents would be glad of the opportunity move out of their “dilpidated, unsanitary shacks”, though some area homeowners fought back against having to give up their homes. The cry of dilapidation was not without foundation: Silver and Moeser’s The Seperate City cites a 1938 evaluation by Harland Bartholomew which found that “approximately one-third of the city’s 43,000 housing units lacked indoor toilets. Nearly one-half had only cold water, and 2,635 units had no water at all.” It takes no stretch to imagine that these conditions were more prevalent in the low-income neighborhoods.

The Richmond Housing Authority was founded in 1940, and the next year work began on Gilpin Court. A 1985 article in the Richmond Times-Dispatch by Bonnie Winston says that:

Attention focused on an eight-block area north of Broad Street in which 319 of 321 structures were judged as substandard beyond any doubt.

In 1941, clearance and construction began on what by the end of 1942 was to become Gilpin Court, named for Charles Sydney Gilpin, a famed black actor who was born in 1872 at 200 Charity St., in the heart of the area. […]

The court was to be the first of three “high-standard, low-rent housing projects,” according to accounts. It was to house blacks, 228 of whose families were displaced by the clearance on the site, which had a “record as a breeding spot of disease and delinquency,” newspapers said.

The construction of Creighton Court and Hillside Court followed Gilpin in 1952. Fairfield Court was built in 1958, Whitcomb Court at this same time period, Mosby Court in 1962, and Blackwell in 1970. This marked the end of the construction of the large communities, as no single development since then has contained more than 60 units.

Between 1999 to late 2001, RRHA demolished 440 public housing units in Blackwell using HOPE VI funds provided by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. In an echo of the initial call for slum clearance in the 1930s, the RRHA described the need for action on Blackwell by stating that:

Over time the units became obsolete and deteriorated. The area was also plagued with crime such as burglaries, robberies and larcenies.[…] The deterioration had led to a high concentration of low-income residents, little retail and a lack of community pride and private investments had all but stopped as private investors remained overwhelmed by the concentration of poverty and public housing that had begun to erode to other areas.

The redevelopment plan also called for the relocation of the Blackwell residents and approximately 540 replacement housing units, of which aspects of both critics of the Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA) say were not handled very well.

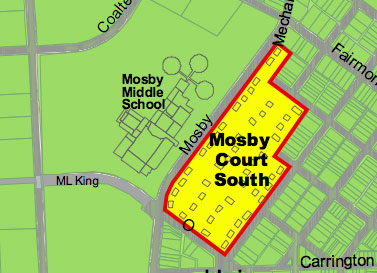

In 2002 the RRHA applied for a $20 million federal grant to demolish the 106 units at Mosby South. The plan was to build “170 units of single-family homes and apartments that would include public housing and units available to the general public” with 105 more units to be built elsewhere in the city. The Richmond Tenant Organization and families from Mosby Court South hired legal counsel to fight against the grant application. The request for funding was denied by HUD in March 2003.

In 2008 RRHA tore down the Dove Court apartment complex in northside and and has plans to redevelop the area with mixed-income single-family and two-family housing.

The RRHA is moving forward with plans to redevelop the Gilpin Court as a mixed-income neighborhood. The area is seen as having a lot of potential due to its proximity to the VCU Biotech Park and Philip Morris, but the plan is not without controversy. A few years in the making already, the RRHA’s Valena Dixon said in early 2008 that, “We know Gilpin Court revitalization will take five to 10 years, and demolition will not start for at least three years.”

Except for the almost $11 million in renovation announced in March 2009, no specific plans have been put forth for Hillside Court or the housing communities in the East End.

RRHA’s 6 largest family developments

RRHA operates six family developments with 400 or more units, four of which are in the East End. The next largest after these six is the 64 unit complex in Fulton.

| COMMUNITY | SIZE | BUILT | AVG.INCOME | AVG.OCCUPANCY |

| Creighton Court (map) | 504 units | 1952 | $9,460 | 8.8 years |

| Fairfield Court (map) | 447 units | 1958 | $9,727 | 9.9 years |

| Gilpin (map) | 783 units | 1942/1957/1970 | $8,158 | 7.8 years |

| Hillside Court (map) | 402 units | 1952 | $8,601 | 6.7 years |

| Mosby Court (map) | 458 units | 1962/1970 | $10,957 | 9.4 years |

| Whitcomb Court (map) | 447 units | 1958 (?) | $9,928 | 8.8 years |

The above date sourced from Demographics Profiles for RRHA Communities.

Nice article – the ave. occupancy data is particularly interesting and telling. Seems to suggest that the projects are not being used as a temporary place to stay while getting back on one’s feet, but rather as a long-term deal where people live for years.

I’ve been curious to know why cities tend to have “projects” and counties / more rural areas do not(?) What benefit does the city get that makes a housing project an attractive way for city managers to spend taxpayer dollars?

I assume the rural/suburban communities formed, in part, to move away from these PWA projects. Counties are then at a financial advantage by forming in ways to avoid these costs.

Bullwinkle, cities get no benefits from having housing “projects”, other than not having even more dilapidated private housing for those persons who live in the “projects”. Counties and rural areas do not have projects because they weren’t needed in the 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s when most “projects” were built. Now everyone sees what a disaster this concentration of poverty is and there’s no way in hell Henrico or Chesterfield would be willing to share their fair share of the low income housing burden for the region because they don’t want to pay for the services they’d have to provide. Henrico and Chesterfield are more than happy to force low income residents to stay in the city lest they have to help deal with the problems of persistent poverty.

I’ve been drawing maps of Woodville without Fairfield Court for years. I can not wait for Fairfield to be demolished and Woodville brought back as a proper neighborhood.

What amazes me is that no one was available to inform the residents of Mosby South the benefits of getting OUT of the projects! And that the plans were scrapped after being sued. What can be done to dismantle this concentration of poverty and disperse that more equitably throughout the area? I know it was done in Charlotte, NC and Atlanta – successfully. And it didn’t take 10 years either! Not even 5 yrs. in Atlanta!

Also, it’s interesting that Blackwell was demolished; being the most recently built in 1970 as compared with those built much, much earlier. If it was in such a state of deterioration, what condition are the neighborhoods built in the 40’s and 50’s?? Policy needs to be changed so that residents don’t stay in these “temporary” situations for nearly a decade, but rather the shorter time frame they were intended. Then maybe the poverty level would go down as people must get on for themselves and move out.

it’s important to keep in mind what demolishing those projects would mean for its current residents. of course they would not be thrilled about their homes being destroyed because there are many families who have lived there for years and years and have no place else to go. the other issue to consider is that we want these impoverished persons to get jobs and get out, but they can’t get jobs because they have to get to them. how do you get to a job interview without a car? the bus right? well say you have no income to purchase bus passes? then you walk. why would you go through all that trouble if you have a house you can live in and food stamps to keep you fed already? hence the increase in crime and selling drugs. it is easier to get a gun in the projects than to get to a ukrops. it’s not totally the people’s fault that they aren’t moving along as we intended them to! it’s poor planning on the location of the housing projects and a lack of programs to help people get on their feet.

There are some really beautiful success stories that come out of these housing projects, but those people have to fight way harder than any of us could ever comprehend to do it. it’s not that the projects themselves were a bad idea-inexpensive housing is essential, but concentrating poverty as the other comments have noted, is not effective. i think demolishing them at this point is too little to late, but what should be done is that when public housing isn’t up to code or in recent cases, burns because of faulty wiring, residents should not be moved back into those houses! instead the government should use the housing choice voucher program and the housing assistance program to get people out of the projects and into better locations which provide better opportunities. anyway, the point is that you can’t just knock down the buildings and expect the problems to go away.

Public housing is a longer-term option for people for a simple reason: there is not enough decent, affordable housing in the private market. To assume that it’s going to be temporary ignores the reality of trying to get a place to live with low income. Section 8 and other low-rent options are not sufficient.

I would be interested to see what the percentage of low-income housing residents is, compared with other cities, per capita. Do we have more poor folks by ratio? If so, why? And when we discover why, we can have a focus toward solution with the situation.

What are other cities doing to foster or not foster government dependence?

Time-frame limitations are appropriate for the able-bodied. That’s not mean. I was told when I needed to begin to repay my gov’t-backed student loans, there is a time limit on the first-time homebuyer tax credit, my mortgage is due on the same day each month, as is my health insurance payment. It’s not a surprise, it’s life.

We live a stone’s throw from Woodcroft and hear major gunfire about 3 or 4 times a week. The kids don’t flinch – they just count rounds, estimate direction, and call the cops. And most people that I know don’t even call the cops. Too used to it. Complacent.

Thanks for posting this, John. Interesting stuff.

#8 jjames. It’s kind of hard to compare “affordable housing” and public housing. The rental amounts that public housing collects from tenants is not sustainable in any “affordable housing” market. Section 8 in my opinion is a good alternative. It gets people out of public housing and puts them into the private market. Which could be another apartment complex or a house. Not that section8 doesn’t come with its own share of downsides, like not enough vouchers. What’s the answer is public housing? Could they get rid of public housing and increase section8 or other similar rent assistance?

You make a very good point about incentivization, Lindsey. If they no longer had public housing paid for by the city, I think many more people would choose to find work instead of becoming homeless. As it stands now, the incentive is to remain on the dole. Take a look at those average income numbers – how many people are consistently unemployed to drive those numbers so low?

Interesting discussion, without the latent racism that so often underlies these discussions. IMO, projects were absolutely essential when they were built; they are equally a part of the problem today. I recommend getting a copy of the RRHA master plan. It calls for phasing out out virtually all project units over the next ten years. VERY controversial in some circles.

Lindsey… what about those people who were displaced when they BUILT the projects? Those houses in Gilpin were not that far gone from pictures I’ve seen. I don’t even think Fulton was as bad as had been written to warrant total destruction. But people were without homes when they claimed that part of Jackson Ward. When Fairfield was built, it destroyed 2/3 of Woodville which had no slums. The houses were not that old and some had just been built. Whitcomb took some of Sebree’s Addition… not much is know about that neighborhood as most of it was destroyed due to Whitcomb, I-64, and industrial developments. Some of the people in public housing abuse it and don’t deserve it. Others deserve better than what they have now. I’m in favor of demolishing all the public housing in favor of mixed-income/mixed-use developments. They won’t be written off completely. It’s time to bring back the neighborhoods that were destroyed by these failed concentration camps.

failed concentration

Very good choice of words.

Prior to the building of the projects, Richmond was much more mixed income and poverty was less concentrated. (Kind of how my bit of CH is now)

Also, while I think this story is interesting and well-written (Thanks John!), it completely ignores the role that I-95 and the destruction of Jackson Ward had in displacing people from their neighborhoods. I-95 could have gone through any number of areas of the city, but it went through the part that was historically African American and then forced the displaced folks into projects. No wonder no one wants to move out of Mosby, they’ve seen what happens when the city dismantles housing and rebuilds.

I was born (1956) and raised in Creighton Court. My uncle was one of the construction workers who helped build it. There were a number of great people that lived in CC. Curtis Hope, to name a few, was an activist for the rights of the black community. The 3rd St. bridge linking downtown and Highland Park was named after him. The Creighton Court Eagles football team won multiple city league championships. We use to play on the construction site of present day I-64 when it came by the hood. Back in the day, we could sleep on the front porch without any trouble whatsoever. Yeah, those were the good ‘ol days long gone. Our ancestors from CC would definitely frown and shed tears at the present conditon of the neighborhood.

how can you guys say that about these places …just because there are one or two bad apples that kill the dream for everyone else of getting help is just out right nasty of you guys im 25…i have to pay 620 in rent…. got laid off from my job and on the brink of lose’n my apt. and mind i need one of these projects to get on my feet my family came from c.c and g.c i just dont understand people ….

Many people who live in low income housing projects lack the skills and education to advocate for themselves and have no idea what lies outside the confines of their invisible gated community. It is important to expose residents to greater opportunities through better education and employment. Poor people deserve quality housing.

Looking for a apartment to live in

With redevelopment of Richmond’s public housing still a distant goal, authority considers interim measures to curb violence

http://www.richmond.com/news/local/city-of-richmond/with-redevelopment-of-richmond-s-public-housing-still-a-distant/article_8203ca3b-2c0e-5b52-92f9-f9043b4729ca.html