RECENT COMMENTS

The Fairmount Historic District

The Fairmount Neighborhood began as a real estate development project in the fall of 1890, one of several contemporary efforts to create new suburban towns just outside the Richmond city limits in Henrico County.

The Fairmount Historic District

- Early Uses

- Fairmount Land Company

- Introduction of the Trolley

- Commercial Development

- Incorporation and Annexation

- 2nd Wave of Development

- Changing Demographics

- Decline and Redevelopment

- Map of the Fairmount Historic District

- Credit and Sources

Early Uses

Initially a speculative project with lots first offered for sale in 1890, Fairmount became an incorporated town for a brief period, from 1902 until it was annexed by the City of Richmond in 1906. It was one of at least ten plans for new Richmond suburbs formulated between January 1890 and January 1891. The other suburban subdivisions appear to have been much better known at the time and to have been more successful as real estate development projects. Other subdivisions created on the outskirts of Richmond in 1890 included Highland Park, Leonard Heights, Lisburn, Montague Heights, Woodland Heights, Brookland Park, Chestnut Hill, and Oak Park. The plans for Barton Heights were announced in January 1891, and several others such as Ginter Park followed after 1894.

One distinction between Fairmount and most of the other new Richmond neighborhoods of the 1890s is geographic: while Fairmount is at the crest of the hill in the city’s east end, most other plans launched in the 1890s were in the city’s northside. Several northside developments were initiated within a short period of time with some overlap in both the boards of directors and the promoters involved.

Some of the new plans, particularly in the outer fringe of the city, had larger lot sizes and lent themselves to grander architectural designs. By the time the plans for Ginter Park were underway, in the mid 1890s, for instance, there was enough interest in larger lots and in constructing larger houses that parcels along some streets in the new subdivision were designed to have 100-foot-wide lots frontages. These areas became showplaces for grand Queen Anne style and Colonial Revival style villas rather than the row house forms that made up Fairmount.

Just a few years prior to 1890, most of the land now occupied by Fairmount was open acreage in modest-sized tracts used for agricultural purposes, including farm fields and livestock holding areas. Several of the rural tracts were owned by local businessmen who operated slaughterhouses (just east of the district), livestock companies, and other agricultural operations that served the Richmond area in the late nineteenth century. The slaughterhouse owners were members of families that had emigrated from Germany earlier in the nineteenth century. At least one family, the Brauers, had grown wealthy as cattle dealers. Two or three other families, such as the Hechlers and the Briels, appear to have located in the area because they were relatives or business associates of the Brauers family. Representatives of these families were among the founding members of the Fairmount Land Company in November 1890.

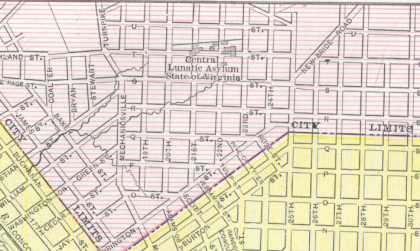

The city’s street grid had been extended, at least in theory, beyond the city limits and across the area contained within the boundaries of the Fairmount Historic District in the early 1800s. The grid is shown covering the Fairmount area on several (though not all) nineteenth-century maps, but most of the lines apparently represented “paper streets” until the Fairmount Land Company was formed in 1890. The street names within Fairmount preserve the naming system of the original Richmond street plan, with north-south streets named by ordinal numbers and east-west streets named for letters of the alphabet. The southern boundary of the district along Carrington Street was also the original boundary of the area that the Fairmount Land Company set out to develop in 1890, and it was also the southern boundary of the area incorporated as the Town of Fairmount in 1902. Despite being an extension of the city’s grid, Fairmount remained separated from the city limits of Richmond by a half-block strip of Henrico County land on the south side of Carrington Street until the 1906 annexation of the neighborhood.

By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the area that is now Fairmount contained a few houses and the campus of a large hospital that had initially been established for the military during the Civil War. On the map of the area in the Beers 1876 Atlas of the City of Richmond, thirteen small houses appear in the southern half of the district (the northern half of the district is not shown), on scattered sites west of 24th Street. The houses may have been sited to correspond to the street grid. They occur on six different streets, often on street corners. There were only two or three houses on each street, except in the 2200 block of Carrington Street, where five buildings are shown near one another. Although elements of these houses may have been incorporated into later designs, no intact pre-1890 houses remain today along Carrington Street or on the streets west of 24th and south of T Street. The parcels where the pre-1890 buildings had been located along Carrington now contain either houses with design elements from the 1890s or later or vacant lots. Bernard Briel had apparently started a small subdivision by that time and is shown as owning most of the land along Carrington Street. Briel is the only property owner identified on the Beers map as owning houses west of 24th Street. At the northeast corner of the area depicted on the map, the homes of John W. Brauer and William Hechler are also shown. They faced 25th Street between T and U Streets; however, neither houses is still standing today On the same map, sixteen houses appear in a row with a few gaps along the east side of 24th Street between Q street and T Street. Most of the houses shown along 24th Street were depicted as larger than the ones on the scattered sites further west.

Although some elements of some of the houses along 24th Street could be incorporated into later designs, only two or three of the buildings are known to be still in existence. They included a double house at 1309 24th Street, which appeared to date from as early as the 1860s and which was demolished in April, 2009.

The Italianate style house at 1125 24th Street may have begun its life as one of the pre-1890 houses. It has proportions that suggest that it was originally a mid-nineteenth century Greek Revival style design, with a fenestration pattern that is slightly asymmetrical reflecting a wider stair hall than what is normally found in this neighborhood. It is the only Italianate style house in the district with such a wide-proportioned façade and the only one with a fenestration pattern spaced asymmetrically this way. However, all of its surface ornamentation indicates that it was completely re-designed in the 1890s with new ornamental details to match the surrounding Italianate style houses (because of this, it has been dated as ca.1895 in the inventory).

The only other building in the district known to be older than 1890 is the ca.1840 house at 1614 21st Street, which is located outside the area shown on the 1876 map. In addition to these buildings, fifteen large buildings are shown as part of the hospital campus at that time, none of which are still standing today.

Some of the parcels where buildings are shown on the 1876 Beers map appear as vacant lots on the map of the area in Baist’s 1889 Atlas of the City of Richmond, especially the houses on scattered sites west of 24th Street. However, by 1889, Bernard Briel’s property along Carrington Street is referred to as “Briel Sub. [Subdivision].” The Briel property appears to contain 40 buildings by 1889, including a few outbuildings. A corner lot in this subdivision contains a larger building labeled as the “J.W. Wright & Co. Tobacco Facty. [Factory].” The Hechler and Brauer houses also appear on the 1889 map, with a few outbuildings that are not shown in 1876. The hospital campus appears to have been reduced to one building by that time. John W. Brauer’s property appears to have been enlarged by that time to include the land north of the hospital campus, but the map does not show the boundaries of his property with any clarity. Isaac Davenport owned a vacant area according to the 1889 map, approximately the block bounded by 22nd Street, 21st Street, Q Street, and R Street. The block located diagonally southwest of Davenport’s land had apparently been subdivided by R. P. Boze by that time into 22 parcels. Several blocks north of R Street had likewise been subdivided into 22 parcels per block by 1889 but contained no houses.

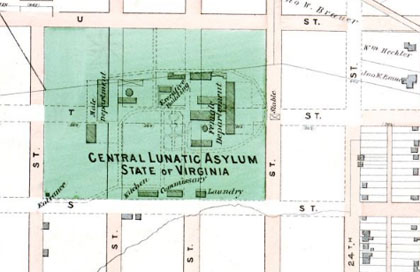

The Fairmount area contained a few non-residential complexes and other developments prior to 1890 that helped to shape the neighborhood as it displaced them. The most important of these was the multi-building mental hospital complex that had been built near what is now the center of the historic district. The hospital had been built using property that had originally been associated with a military hospital during the Civil War. The campus of the Central Lunatic Asylum occupied an area that covered three blocks by a block and a half. The southern edge of the grounds was S Street, which later became Fairmount Avenue, the main street of the neighborhood. The facility was relocated to a rural site near Petersburg, Virginia, in 1885. When Fairmount School was constructed, about 1895, a piece of land just north of center in the asylum grounds was chosen as the site for the new school (the asylum buildings had apparently been demolished by that time, but some of them appear to be shown as late as 1890 on the Beers Map of Richmond, Manchester and Suburbs). When the Fairmount Land Company laid out its development area, most of the lunatic asylum site was included, although the future site of the school remained just outside the platted area. The boundary followed the same line when the Town of Fairmount was incorporated, leaving the school out of the corporate limits, in Henrico County. However, the neighborhood’s rows of houses extended beyond this line as early as the 1890s, and the developed area continued to grow a few more blocks in the 1920s, so that the school became the center of the neighborhood. The neighborhood now clearly extends as far to the north of it as it does to the south, with the school at its center.

Another land use that predated and helped shape Fairmount was the Fairfield Race Course, a horse-racing facility built prior to the Civil War at what is now the neighborhood’s northeast corner. (It may have fallen out of use by 1890, as it was referred to as “Fairfield Old Race Course” on the Beers 1890 Map of Richmond.) The race track comprised a 15-block area, most of which is now the adjoining 1950s neighborhood of Peter Paul, but its presence, covering several blocks of what is now the northeast corner of Fairmount, appears to have delayed development in the area until at least the 1910s.

The Fairmount Land Company

The creation of speculative land companies to subdivide large tracts and start new communities was a growing national trend in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Like Fairmount, many of the developments were located just outside the established boundaries of a growing city; therefore, it was normal to assume that the new community would take the form of an independent new town. Although the developments were almost always promoted as if they already were “towns,” the actual creation of a formal municipal government was a step to be taken by the residents and their representatives several years later, when the development was successful and independent government was appropriate. Until the parcels were all sold, the development projects were driven by the corporate board of director of the land company, usually a small group of investors, including one or two local landholders, who staked out the undeveloped areas and incorporated themselves as “land companies.” The land company’s directors and/or stockholders often included attorneys, experienced promoters, and wealthy investors. Fairmount followed the usual pattern but without much fanfare.

The Fairmount Land Company was incorporated on 10 November 1890 in the Circuit Court of the City of Richmond. It was founded by at least three individuals: John H. Dinneen, S.S.P. Patterson, and Frederick C. Brauer. Dinneen had been a major in the Civil War, serving under Col. Henry C. Jones as an inspector-general in the First Virginia. He had also laid out a small speculative plan near the heart of the city in 1889. Brauer was a wealthy cattle dealer from the Fairmount area, a representative of one of the several families with German surnames that owned land in the area prior to 1890. Patterson was a local real estate attorney. Dinneen, Patterson, and Brauer served as trustees holding the initial assets of the company in trust on behalf of a group of stockholders.

The land company purchased tracts of land from at least eight individuals or families to assemble the area that was to become the new community. The purchases were made in October and November of 1890, most of them before the formal incorporation of the company. Since the initial land transactions occurred before the company was formally chartered, and the title to land was therefore in the name of the trustees rather than the corporation, the company reorganized in April 1891 to record a new deed to transfer the ownership of unsold lots to the corporation as a whole. Dr. John Mahoney was vice president of the Fairmount Land Company at the time of the transfer of the title for the unsold parcels to the corporation. The other officers and stockholders are not named in the deed, but it appears from the way the prior land transactions are described that several representatives of families who had sold land to the company were stockholders at this time, perhaps having traded some land for stock when the company was forming.

The neighborhood provides physical evidence for what happened next. Hundreds of nearly identical frame houses were built in the first wave of construction, indicating that a large percentage of the district, possibly as much as 50 to 60% of the housing stock now standing, was built in the 1890s, most likely between 1890 and the onset of the Panic of 1893. With the financial crisis, development in the neighborhood appears to have slowed down or stopped. In some ways, the Panic of 1893 was a short adjustment of the national economy. However, the national economy experienced dramatic swings for several years after the panic and the economy did not fully recover until about 1897.

By the time the economy recovered, styles had changed, largely influenced by the Columbian Exposition of 1894. After 1894, it was much more common to lay out new neighborhoods with winding or radial streets and aesthetically placed park spaces and to design each house as a freestanding unit so that it could be seen from a variety of angles. Ornamental façade treatments became more common on what earlier generations had often treated as unadorned side elevations. Fairmount typifies the pattern for modest-sized houses just before the panic, while larger houses on some streets in Ginter Park in Richmond’s northside, for instance, typify the pattern that emerged after 1894.

The names of the builders who built houses in Fairmount in the first wave of construction are not known on a building-by-building or block-by-block basis. However, the names of one or two builders and/or lumber dealers associated with the neighborhood at the time are known. The locations of several lumber yards that were in the neighborhood between the 1890s and the 1920s are shown on Sanborn maps of the neighborhood. In conjunction with this, the building stock provides some evidence of which buildings were built together as groups.

Before 1890, R.P. Boze owned the block bounded by 21st Street, 20th Street, O Street, P Street, and Carrington Street (just outside the southern tip of the district boundary). By 1889, this block had been subdivided into lots, as mentioned above. However, the lots were apparently not all used for building homes. Instead, the eastern half of the block became the location of the W.P. Boze Lumber Company. Although it is not known for certain what role the Boze Lumber Yard played in the development of the neighborhood, the lumber yard, the largest of several in the neighborhood, remained in place through the 1920s. In an oral history interview conducted for the Church Hill Oral History Project, Edith Toliaferro indicated that her father ran this lumber yard for Mr. Boze for many years, while the owner lived out of the area.

The Italianate cornice details (including the perforated ventilation panels) found in the neighborhood correspond closely to details shown the 1882 patternbook of the J.J. Montague Lumber Company, located at 9th Street and Arch Street in Richmond, near the Manchester Free Bridge. Several other details commonly found on houses in Fairmount appear in this publication. It is not known whether the details were actually from the Montague lumberyard: the drawings and patterns from Montague’s pattern book could easily have been copied by other lumber companies in or near Fairmount, a common occurrence among lumber companies then and now, since the shapes are not patented.

In addition to the Boze Lumber Yard, several other smaller lumber companies operated in Fairmount by the 1920s. These included a second hand lumber yard in the block bounded by Q Street, R Street, Mosby Street (Mechanicsville Turnpike), and 19th Street, just west of the district, and another lumber yard at the corner of Mosby and Fairmount Avenue, both of which were just west of the district boundary. A small operation dealing in coal and wood was also located at the corner of 22nd and Carrington Streets in the 1920s. However, while it stands to reason that these lumber companies had customers in Fairmount and may have been in the business of building whole houses or groups of houses there, no definitive documentation has been found of who built what. The only builder known for certain to have lived in the neighborhood was a man named J.T. Nuckols, who indicated in a 1906 newspaper article in the Richmond Times-Dispatch that he had lived in Fairmount for 15 years. Nuckols expressed concern that fire protection was needed in the neighborhood because the houses were all frame and located so close to one another.

While Fairmount’s architectural evidence is more indicative of typical development patterns in the first half of the 1890s than of the second half, there was an ongoing interest throughout the decade in maintaining the development of the neighborhood. Real estate advertisements from 1893 indicate a renewed campaign to sell the remaining parcels when the economy appeared to be pulling out of the panic.

Although in 1890 Fairmount appears to have been lost in the long list of newly launched neighborhoods, by 1893, it was well enough known that real estate ads for individual parcels or small subdivisions a few blocks beyond its bounds contained references to it. An advertisement that appeared in the Richmond Times on 4 April 1893, offering a tract of land for sale near Fairmount with existing house, says:

“very close to Fairmount and Sebree’s Addition, will subdivide to great advantage into building lots, and can be soon sold at great advantage…. Do not forget that the effects of the collapsed boom have about worn off; that the city, with its healthy and rapid growth, is bursting out into the suburbs over its circumscribed boundaries; …and that nearby land, such as this is, will soon be wanted as home sites.”

The Introduction of the Trolley

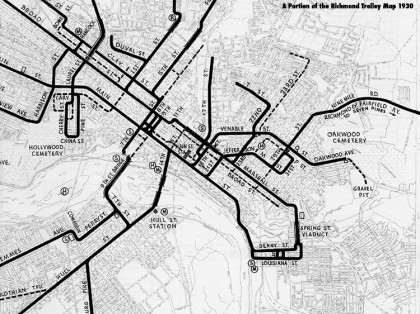

A major factor in suburban development when Fairmount was conceived was the introduction of electric streetcar lines connecting various parts of Richmond and making new areas more accessible for residential neighborhoods. The Fairmount development project was driven more by the anticipation of new lines than it was by lines that had already been built. By 1888, Richmond had the first large-scale electric streetcar system in the United States. Richmond led the nation in the electrification of streetcars, and other cities used the Richmond system as a model for their systems.

The new electric cars came hand-in-hand with extensive planning of new subdivisions. Lines were built to access undeveloped areas and to make established neighborhoods easier to reach. Some new subdivisions were laid out along the lines that had just been built, while others were laid out in anticipation of their completion. Within a few years, several lines climbed the Church Hill streets to the hilltop neighborhood of Fairmount.

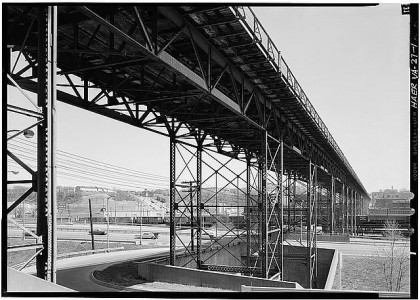

Beginning about 1910 when a viaduct was constructed over the Shockoe Valley, streetcar lines also crossed directly from downtown Richmond to Fairmount without having to climb through the steeper streets of Church Hill. By 1898, Fairmount had two or three routes leading to stops at the edges of the neighborhood. Within a few more years, at least one or two lines crossed through the center of the neighborhood.

In this era, it was also common for individual neighborhoods to form their own streetcar companies to raise capital and construct short lines that connected residences to neighborhood commercial areas and to other transportation systems. Being a new community at the edge of a large city, Fairmount did not have much control over the operation of the larger streetcar systems, but it could start its own neighborhood system. In 1896, community residents established the Fairmount Traction Company and built a north-south line through the center of the neighborhood along 23rd Street. The line began at Venable Street (a half block south of the district) and continued past Fairfield Avenue (which lies a half block north of the district).

In the greater Richmond area, ten or fifteen independent streetcar companies were in operation by the early 1890s, but the companies with the most important lines around the city were consolidated into larger organizations beginning about 1890. In April 1900, in a second wave of consolidation, the newly chartered Richmond Passenger and Power Company absorbed the Fairmount Traction Company. A 1905-1907 map of sewer lines in Fairmount shows another streetcar company’s line running north along 22nd Street to T Street and then west on T Street to Mechanicsville Turnpike, but it does not show the 23rd Street line, suggesting that the Fairmount Traction Company’s tracks had already been removed. A streetcar map published around 1930 shows a dotted line on 23rd Street where the Fairmount Traction Company’s line had been, indicating it was the location of a route that had been discontinued.

Commercial Development

There is some evidence that some of Fairmount’s early leaders may have expected the town to have its own commercial core area. The way parcels were laid out along Fairmount Avenue, which served as the neighborhood’s main east-west through street suggests that the land company had that street in mind for commercial storefront buildings. However, the neighborhood was apparently very slow in developing commercial outlets of any size.

Neighborhood grocery cropped up in a dozen locations, apparently serving localized areas within Fairmount, but only a few larger commercial buildings ever got built. The one extant building that conforms to the storefront prototype of the 1890s and appears to have been built anticipating that a row of commercial storefronts might be built around it is 2125 Fairmount Avenue (at the corner of Fairmount Avenue and 22nd Street). This three story brick building with a recessed corner entrance was a drug store through most of its history, although it is now vacant and boarded-up.

A row of seven contiguous one story storefronts developed on the north side of Fairmount Avenue in the 1800 block by the 1920s. Six out of the seven storefronts were constructed in a matching style around 1925, while one parcel toward the middle of the row contains an older frame building. The frame building follows a Queen Anne style design that was used in three or four other location in the neighborhood.

None of the commercial buildings on Fairmount Avenue appear to remain in their original use, and as consequence of conversion to new uses (such as a storefront church at 1814-1818 Fairmount Avenue, The Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ), the storefront display windows have been greatly altered. Only one or two commercial buildings were constructed on Fairmount after the period of significance. The most notable example is Chiles Funeral Home, a ca.1960 building at 2100 Fairmount Avenue. It resembles a hip-roofed Ranch style home, only at a much larger scale.

Most of the neighborhood stores on scattered sites have been vacant and boarded-up for many decades. A key exception is the Church Hill Super Market, a relatively plain brick commercial building at 1306-08 22nd Street, still actively operating as a grocery store, although most of the storefront display window area has been closed in with brick. Another very active neighborhood grocery serves the northern end of Fairmount. Known as Crenshaw’s, it is located in a Craftsman style bungalow at 1801 22nd Street. Although the design of Crenshaw’s suggests that it is a converted house, the building has been a store since at least 1925 according to Sanborn Maps, approximately the time in which the building would have been built.

Since Fairmount Avenue did not become heavily developed with commercial buildings, it provided an excellent location to build churches and larger houses in the early generation of the neighborhood. One of the neighborhood’s finest Queen Anne style houses, for instance, was built at 2001 Fairmount Avenue. It features a cutaway bay and a porch with layers of sawn wood ornament. Although other houses on this model were built in other locations in the neighborhood, this is the best preserved example of its type.

Two brick Queen Anne style houses were built side-by side at 2201 and 2203 Fairmount Avenue. They are among only a handful of brick houses in this style constructed in the first decade of the neighborhood’s existence. While similar houses were built on the same model in frame, the Fairmount Avenue location seems fitting for the only ones of this pattern built in brick.

Incorporation and Annexation

Fairmount quietly matured between 1890 and 1902. By the beginning of 1902, the Virginia State Legislature passed an act incorporating the subdivision as a town. By this time, the state government had begun to define an incorporated town as a municipal unit with taxing powers, a council, and a mayor, but still governed and taxed in part by the county in which it was located.

The act of 10 March 1902 explains how the town was to function, including how the mayor and council were to be elected, how taxes were to be levied, how streets, sidewalks, and sewer lines were to be installed and maintained, and similar guidelines. The act also states that T. Walker Jeter was to be the first mayor of the town and it names the five initial members of town council. As part of the legislation, the following municipal boundaries were set: Mechanicsville Turnpike, Q Street, the property line of William H. Brauer (an east-west line just north of T Street), 23rd Street, T Street, 24th Street, and Carrington Street (the area so-described constitutes the southern half of the historic district, from the school building south).

In 1904, the state legislature acted again, amending Fairmount’s incorporation. The amendment’s purpose appears to have been to state that the mayor and council shall receive no salary, that town ordinances may include levying fines, that parents can be fined when their minors commit offences, and that with a three-fifths vote, council may borrow money by issuing and selling bonds.

Also in 1904, Fairmount installed sewer lines. The lines were designed to connect to the city’s nearby main sewer. The connection to the larger system was not made in 1904 because the city was under no obligation to provide this service and the area would have had to be annexed to complete the connection. During a hearing about annexation two years later, Fairmount’s mayor testified that the town’s water and sewer lines “were made to conform to Richmond’s water and sewer lines in anticipation of annexation.” It was clear at this point that the government of the newly formed town was using its municipal powers to build its infrastructure ultimately as part of a scheme to see the Fairmount area annexed into the city limits of Richmond and thereby enjoy services only the city could provide to it.

In 1905, Fairmount’s leaders apparently asked the city to annex it. Both the city government and the governing body of the town of Fairmount were in favor of annexation, claiming that the majority of Fairmount’s citizens were also in favor. The project might have moved forward without much opposition, except that because Fairmount and Richmond did not have any common boundaries, the annexation required including an area that was county land, in neither the city limits nor within the town boundaries. Part of this was a narrow strip of land along Carrington Street that separated Fairmount’s boundaries from the city limits.

Another piece of Henrico County land in the area proposed for annexation was a larger tract that belonged to Major James H. Dooley and his wife, S.M. Dooley. Maj. Dooley was one of Richmond’s more prominent citizens of the time, and he and his wife were prominent forces behind numerous philanthropic projects at the time and in the ensuing decades. The Dooleys opposed the annexation project and took the matter to court. Henrico County, in the process, decided it was not to its advantage to give up the territory in the proposed annexation area, and Maj. Dooley found several others who opposed the project for other reasons.

These included John P. Branch, an elderly Richmond banker, who testified against the annexation project because adding the territory would cost Richmond too much in the long run. Mr. Branch presented his own calculations to the court to demonstrate that the annexation project would result in higher taxes for all Richmond citizens. N.W. Bowe also opposed the annexation.

Bowe was a wealthy Richmond realtor and real estate auctioneer who had been closely associated with numerous real estate development projects in the Richmond area. He gave the court his own estimates of how the annexation would raise Richmond’s tax rates. One of the issues brought up in the case was the question of how much benefit annexation had provided previously to the Lee District, now the part of Richmond generally known as “The Fan.” The Lee District had been annexed 14 years earlier, and the annexation had been promoted on the basis that it would provide much better street maintenance and other services for the neighborhoods in the district. However, all testimony given at this time suggested that the promises offered to the Lee District had not panned out by that time and that the area’s streets and services were generally in worse condition than they had been prior to annexation.

Several of Fairmount’s leaders testified in favor of annexation during the 1906 trial. Their testimony, as reported in brief statements in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, provides a sense of how Fairmount residents at the time saw their neighborhood. J.T. Nuckols, who the paper says was a contractor, testified that he had lived in the neighborhood for fifteen years and owned property there. He was in favor of annexation because: “Most of the houses in Fairmount are framed buildings on small lots and near together. Fire protection is greatly needed.” Although the article does not say whether Nuckols actually built any of these houses, it does say he was contractor and a property owner there and it shows he was concerned about the neighborhood’s design characteristics.

Bernard Gallagher, then mayor of Fairmount, testified for annexation. As part of his testimony, he stated that there were 257 houses in Fairmount at the time and 600 houses in the adjoining territory to be annexed. Walker Jeter, Fairmount’s prior mayor and the first person to hold the office, also testified in favor of annexation.

The discussion of the houses in the territory adjoining Fairmount (apparently to the east and west, along R Street and S Street, and along streets that crossed them just outside the Fairmount district) brought in a poignant discussion about race in Fairmount. Like many new suburban plans in the era, a common clause was inserted as a covenant in the deeds for parcels sold by the Fairmount Land Company barring future owners from selling the real estate to “persons of African descent.” (Clauses of this type remained in the property documents of many suburban neighborhoods until they were determined to be illegal in the 1960s.) However, the clause itself was not the focus of the discussion.

During Mayor Gallagher’s testimony, the mayor mentioned that Fairmount had 1,500 people at the time, “all white except one negro family.” The 600 houses in the adjoining territory, however, included “the little one room shacks of which there are many,” and about 1,200 people including negroes (the implication being that there were many more African Americans in the adjoining area). Upon hearing that Fairmount had only one African American family, the judge expressed surprise and asked “How in the world do you keep the negroes out?” The mayor’s reply was that ‘We just don’t or sell them houses or lots.” After annexation, the population of the neighborhood gradually became predominantly African American, as explained below.

The arguments against annexation did not prevail, and Fairmount, along with an area to the east and west of it, was brought into the Richmond city limits in early 1906. Maj. Dooley’s property was specifically excluded from the area by tightening the boundaries. Some other large tracts of land near it were also removed from the area originally proposed.

During Fairmount’s brief era as an incorporated municipality, and after it became annexed to the city, the neighborhood was maturing, but development had slowed and apart from the coverage of the annexation hearings, the community was apparently not very newsworthy. Neither the act incorporating the town, nor the act amending the incorporation was given any coverage in the Richmond newspapers. The number of buildings in the district dating from approximately 1900 to 1915 indicates slower growth in this period than in either the decade before or the decade afterward. The community may have been appointing leaders, pursuing legal status from the state assembly, studying ideas for new infrastructure, looking toward maintaining law and order, and pursuing annexation, but the signs of growth, as reflected in the housing stock, are scant from 1900 until approximately 1915, when the neighborhood would begin to take off again.

Second Wave of Development and Afterward

About 1915-1925, as a City of Richmond neighborhood, Fairmount experienced a second period of substantial growth. Like the earlier generation, a few builders, either working as speculative developers or offering pre-designed packages to families, apparently built most of the new houses. Nearly 100 new buildings were constructed in a short period of time. Along some streets (especially in the north, where a few whole blocks of land were still open for development), the same design was often repeated between five and fifteen times in a row, sometimes lining both sides of the street.

In all, about 80% of the new houses built in this wave were built following three or four designs, suggesting that no more than four builders were involved, although the names of the builders are not known. Most of the remaining 20% are similar in design, generally modest-sized frame bungalows.

In some blocks, the bungalows and other small houses vary enough in design to suggest that the entire block was built parcel-by-parcel by home owners, or possibly in some cases by developers who owned only one parcel here and another parcel there. The new development projects of this time period included three Craftsman style bungalows on Fairmount Avenue (at 1900, 1902, and 1906 Fairmount Avenue) and six identical houses along 20th Street that match those on Fairmount Avenue (at 1401-1413 20th Street).

Two other groups of bungalows following repeated designs are found in the 1800 block of 22nd Street. On the west side of the street, the repeated forms are one story frame houses with asymmetrical side- gable roofs that resemble the false mansards of a generation earlier in form, but unlike the earlier one-story false mansard houses, these have Classical Revival style porticos across only one half of each façade, marking the entrance. Every other portico has a front-facing gable detailed as a pediment, while the houses in between have flat-roofed porticos.

A little further north in the 1800 block and throughout the 1900 block, the bungalows are one story brick forms with gabled roofs. The gables alternate in design so that some are front gables, some are side gables, and some are clipped gables. This same form occurs in the 1800 block 23rd Street, as well. The houses are so evenly spaced and so similar in design on both of these streets, in spite of the alternating use of details, that the conclusion seems inescapable that they were all the product of the same builder or lumber company. Comparison of the 1924 and 1925 Sanborn Maps for the city indicates that were all constructed in the mid 1920s. With approximately 30 houses following the same two or three patterns in the 1800 and 1900 blocks of 22nd and 23rd Streets, this development accounts for about 30% of the new buildings built in Fairmount’s 1915-1925 period of growth.

Changing Demographics

Little information has survived about the social and domestic activities in the neighborhood in its first sixty or seventy years. It was apparently a mostly Caucasian residential community until the 1930s. The city’s 1934 Master Plan indicates that by that year, African Americans were in the majority in approximately half of the city blocks south of Fairmount Avenue. North of Fairmount Avenue, however, only a few blocks along 24th Street were predominantly African American (apparently in the 1300 block, where the small one story houses are located; the fact that this was a dead-end street at the time combined with the small size of the houses to reinforce the segregation pattern). White residents predominated in 1934 in almost all other blocks in the district north of Fairmount Avenue.

The racial mix of the neighborhood was affected both by the fact that it was surrounded by African American neighborhoods and by the segregation policies that came into the spotlight in Virginia just before the official segregation of public schools became illegal nationally. In Richmond’s 1946 Master Plan, Fairmount Elementary School (which had been renamed as “Helen Dickinson School” in 1925) was expected to be a school for white students into the foreseeable future. However, by 1958, the plan had changed and the school was designated as an African American School, with the name changed back to “Fairmount Elementary School.” The white students were apparently sent to Bellvue School and Springfield School, the nearest all-white elementary schools at the time. Bellvue School was at 22nd Street and Grace Street and Springfield School was located at 26th and Lee Street.

Although the evidence is that Fairmount had white sections and African American sections prior to 1958, the neighborhood appears to have become a predominantly African American community almost immediately after the school was officially designated for black students only. Around the same time that Richmond made this designation, a number of churches, apparently historically white congregations, left the neighborhood to build new buildings a few miles away. This may have been the result of membership growth, relocation of most members to newer suburbs, or just the desire for new buildings; however, it is also a pattern that typically indicates a change in racial demographics in the 1950s and 1960s.

The decade was also a time of heavy development of large-scale public housing communities in the East End, beginning with the construction of Creighton Court in 1952 followed by Fairfield Court, Whitcomb Court, and Mosby Court.

Eventually the older church buildings in the neighborhood were sold to predominantly African American congregations. As an example, Fairmount Baptist Church, the congregation that built the brick buildings at 2011 and 2013 Fairmount Avenue, had either moved or folded by 1958, at which time a congregation known as Mt. Tabor Baptist Church moved into the building. In addition to changes in ownership at all four of the churches on Fairmount Avenue and two others in the northern half of the district, at least four other congregations built small churches in the neighborhood between about 1950 and 1985.

Apart from the four or five new churches, plus a funeral home building and a few modest houses, Fairmount saw almost no new construction between 1950 and 2000. Two brick churches in northern part of the neighborhood were built about 1950 in relatively high style designs. One of these is the former church of the Nazarene (now The Church of God) at 1601 21st Street, a buttressed Gothic Revival design on a raised basement. It has some unusual brick work in the window arches, which are almost but not quite pointed (the church has a date stone saying “The / Church of God / Dec. 27 1962,” but it appears that this building was built before that for the earlier congregation).

The other is a high style Colonial Revival Church building at 1719 22nd Street, currently St. Peter’s Episcopal Church (according to the Sanborn maps which were revised about 1950, it was previously a Pentecostal Church; the exact date of construction is not known). The churches also include at least two concrete block buildings: Unity Sanctuary Church of the Lord Jesus Christ, at 1101 20th Street, built about 1950; and Mt. Zion Baptist Church (formerly Little Mt. Zion Baptist Church) at 1607 22nd Street, built about 1955. At least one historic house is being used as a church, but it shows no evidence of architectural changes on the exterior (St. Luke’s Holy Church, at 1400 21st Street).

Two brick churches were built in the 1960s and 1970s: Solomon’s Temple F.B.H. Church of God at 1118 20th Street, built in 1960; and Faith Holy Deliverance Church at 1022 22nd Street, built in 1973. In general, the church buildings reflect the cultural demographic changes in the neighborhood as it became a predominantly African American community.

Decline and Redevelopment

By the 1980s, the building stock in the neighborhood was showing signs of decline and many houses were vacant and boarded-up. In 2000, the City of Richmond launched a new program called “Neighborhoods in Bloom” to provide funding for construction of new houses or rehabilitation of existing ones in six city neighborhoods, including Church Hill (which, for this program, is defined as including Fairmount). Since that time, the city has helped to construct at least 31 new homes and to rehabilitate 13 existing homes in Fairmount, almost all of which lie within the boundaries of the Fairmount Historic District. The new houses built by this program are specifically located in the southern half of the district, south of T Street.

The city found ways to produce house designs that mimic house forms and styles that typify the neighborhood, generally modeling the new houses on prototypes from the 1890s, but using modern materials. For instance, a typical technique has been to use asymmetrical roof trusses to construct a side-gable roof where the front face is steep enough to resemble a false mansard, matching one of the most common details of Fairmount’s historic facades. Although these buildings are not contributing resources, many were built in gaps in the historic street wall reinforcing the urban form that characterizes the historic district.

The city’s program appears to have been successful at spurring other privately funded rehabilitation activities, as the neighborhood has a large number of recently restored houses beyond the ones funded through the Neighborhoods in Bloom program. Recent initiatives in Fairmount have generated an unusual amount of construction activity in the neighborhood; however, quite a number of Fairmount’s historic buildings remain vacant, boarded-up, and in poor condition.

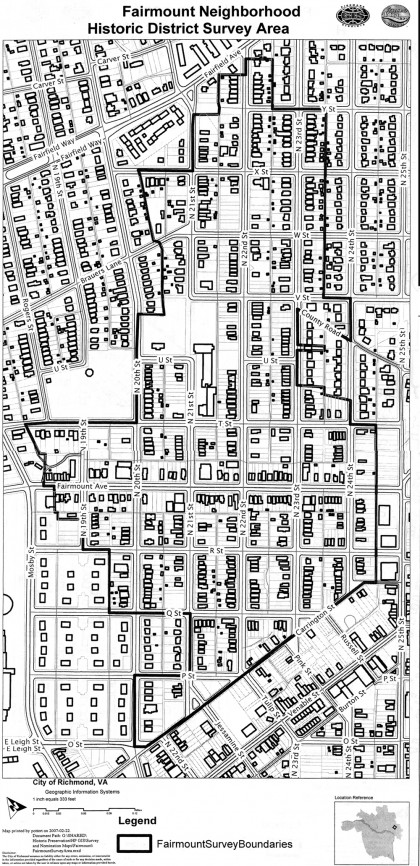

Map of the Fairmount Historic District

Credit and Sources

The text above is almost entirely sourced from the the registration form from the Fairmount application to the National Register of Historic Places (PDF). The original document, dated June 2007, was put together by Terry Necciai, Kirstin Falk, Donna Seifert, Amanda Didden, Cynthia Vollbrecht, and Arianna Drumond of John Milner Associates, and includes much more more than is shown here. Check out the original form to learn more about the Fairmount Historic District, or read up on any of the other sites in Richmond that are listed on the National Register.

The map of the historic district was provided by City of Richmond. The 2008 photo of 1309 North 24th Street is by Cameron Holmes. The trolley map is from Carlton McKenney’s Rails in Richmond. The 1897 Craw map of RIchmond and Manchester is from the collection of John Murden. The 1877 Beers map of RIchmond is from Historic Map Works.

The photo of the Fairmount bungalows are taken from a presentation by Terry Necciai. The photo of the Marshall Street Viaduct is from the American Memory from the Library of Congress. All other photos are by John Murden.

Wonderful, John.

Good job John. I’m glad there’s a district. The boundaries of the town did not extend too far past V st when County Road and Brauer’s Lane used to connect. The house at 1614 N 21. has always baffled me. I haven’t seen it on any maps if it’s that old. Maybe I can re-examin the maps. However, that house was on the outskirts of Fairmount. Where Crenshaw’s is and the two blocks up 22nd St between X and Fairfield… I wanted to study that more. They’re built on Peter Paul’s land but not a part of the subdivision as they predate it. There’s a lot I’m going to have to research… but this helps me a bit too. Fairmount Baptist moved to a building on Mechanicsville Turnpike at Springdale, just north of Henrico Plaza. Mt. Tabor moved from Woodville as Fairfield Court destroyed the original church.

John- interesting article. The first picture is my grand-parents home at 1909 Fairmount Ave. They moved into the home around 1917 and the home remained in the family until the 1960’s. My mother and uncle enjoyed the article – as they took a visit on memory lane. My grand-father J E Reynolds was the City Harbormaster. Thanks for the visit back to the neighborhood that I enjoyed in the ’40’s and 50’s.

Beautiful history! We hope to live in the district some day.

There are plans in the works for some renovations on Fairmount, so it could be a possibility soon.

Maybe you can help. Any ideas on an old Restaurant called The Victory Restaurant in this general vicinity? Off old (1923) Richmond Petersburg Turnpike. Thanks, Paula.