RECENT COMMENTS

The Church Hill North Historic District

The Church Hill North Historic District

- Maps of the Church Hill North Historic District

- Introduction and Early History

- Development in the Nineteenth Century

- After the Civil War

- Decline and Renewal in the Twentieth Century

- Credit and Sources

Maps of the Church Hill North Historic District

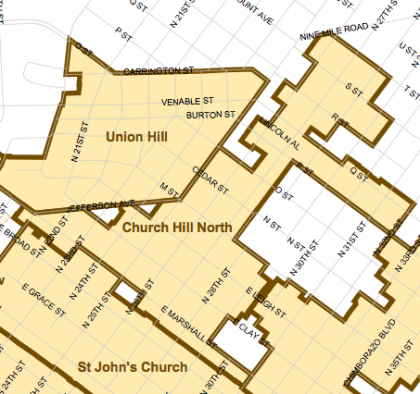

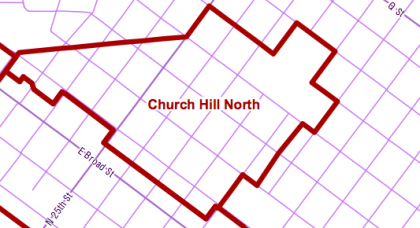

The first map indicates the boundaries of the Church Hill North Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places. The second map indicates the boundaries of the Church Hill North Old & Historic District, a Richmond-specific designation.

Introduction and Early History

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Church Hill North began its slow development as a neighborhood of middle-class merchants and tradesmen, many of whom either were involved in the tobacco trade, or were associated with businesses in the vicinity of Rocketts, the nearby port of Richmond. The dwellings these residents built reflected their station in Richmond society. Solid but modest citizens, their homes often expressed the vernacular and transitional flavor of various nineteenth-century architectural styles.

With the end of the Civil War and the annexation of Church Hill North by the city of Richmond, the land surrounding much of the older homes, was filled in with rowhouses built in the latest styles. For that reason, examples of Federal, Greek Revival, Italianate, Second Empire, Queen Anne, and Colonial Revival styles exist in close proximity with each other. By the turn of the century, the area was largely developed and with the potential for further growth at an end, Church Hill North reached its zenith of stability. While it remained a viable community into the next century, Richmond’s expansion to the west helped to trigger its eventual decline. It is perhaps this westward expansion of Richmond that allowed Church Hill North to survive the twentieth century largely unscathed by intrusive modern construction.

North of Richmond’s St. John’s Church Historic District is the adjacent neighborhood known today as Church Hill North. The area is distinctly different in building material construction from the portion of Church Hill that surrounds Richmond’s oldest and most historic church. It is, nevertheless, one of Richmond’s most interesting neighborhoods. Both Mary Wingfield Scott and Paul S. Dulaney, two noted historians of Richmond architecture, explained that as a neighborhood Church Hill extended far north of Broad Street. In his book, Dulaney included a map of historic neighborhoods which depicts M Street as the northern boundary of Church Hill. Michael W. Gold, the former managing director of the Historic Richmond Foundation, after much research into the population patterns and architecture of the area, suggested the following about the boundaries for Church Hill:

Twenty-first Street and Jefferson Avenue, M Street to the alley between Twenty-seventh and Twenty-eighth and South to Leigh Street to Thirty-first Street, then south to Libby Hill.

Thus, with the exception of the four blocks lying north along Leigh Street, which both Scott and Gold place in a separate neighborhood commonly known as Shed Town, Church Hill North accounts for the remainder of that portion of historic Church Hill not located in the St.John’s Church Historic District, which is adjacent to and directly south of this area.

Historically, both sections of Church Hill shared a similar beginning. In 1737, when Major William Mayo laid out Richmond’s original grid system of 32 squares, St. John’s Church occupied the northeastern portion of that grid, while “to the north and east, large tracts of land were reserved for suburban ‘villa’ establishments.” In 1769, the year in which the western part of Richmond was annexed, Isaac Coles, the only inhabitant of Church Hill, sold his holdings in the area, along with large parcels of land northeast of Church Hill, to Col. Richard Adams. Sometime around 1787, Adams divided his land, called Spring Garden, into several lots and shortly thereafter, when Virginia’s capital was moved from Williamsburg to Richmond, Adams lobbied the governor, Thomas Jefferson, in an attempt to secure the location of the new capitol on hisproperty. Adams was unsuccessful in his bid, and up to 1809 Church Hill was still largely an Adams settlement.

Still, Adams continued to believe that Richmond would expand to the east. In order to promote the development of his property, he maintained the grid street system that Mayo had begun.

Development in the Nineteenth Century

After Adams’s death, his heirs began selling off his vacant property for construction. By 1812, the earliest house remaining in Church Hill North was built at 407 North 27th Street by Charles Wills. A ship’s captain, Wills owned the entire block upon which he constructed numerous outbuildings. None survive except the grocery store he built on the edge of his property at 401 North 27th Street. Constructed no later than 1815, this structure is believed to be Richmond’s oldest commercial building.

It was during this early period that the differences in socio-economic status and dwelling types between the two neighborhoods in Church Hill began to develop. Contemporary with the Wills House in Church Hill North was the Adams-Van Lew House, which stood at 2311 East Grace Street in St.John’s Church Historic District. Although demolished in 1911, the Adams-Van Lew House was an impressive residence built in 1801 by John Adams, a mayor of Richmond and the son of Richard Adarns. In the 1830’s the Federal-style structure was enlarged and embellished by John Van Lew until it became possibly the finest house in Church Hill, rivaling many of Richmond’s best homes in its elegance.

During the nineteenth century, many houses built throughout Church Hill were roughly equivalent in style and importance, but it is this early absence of the truly imposing residential buildings that underscores the differences in the two neighborhoods. Church Hill North would never claim citizens as wealthy as John Van Lew, and it would never boast houses asmagnificent as the Adams-Van Lew House, or its rivals in Richmond’s Court End. Instead, it would remain a neighborhood of “small tradesmen, most of whom owned their home.” As the century progressed, these middle-class residents introduced another distinction that separated the two neighborhoods; the choice of wood rather than brick as the preferred building material would emphasize the social and economic differences that separated the two neighborhoods.

Following the lead of Charles Wills, building continued at a steady pace over the next five years, and a total of twelve structures remain today that were constructed before the Panic of 1819. Typically, these houses are of brick laid in Flemish bond, and are two-and-a-half stories tall with steep gable roofs. They have sidehall plans and three-bay-wide facades. Two of these earliest houses, 501 and 509 North 27th Street, were built respectively by John Parkinson, a clerk at Rocketts, and his brother-in law, Barthlomew Graves. By 1819, the city directory reveals that 26 citizens lived in this portion of Church Hill, and a tavern, kept by Archer Meanly, was listed between Leigh and M Streets on 30th Street. Unfortunately, no trace of this early public building exists today.

Although the building trade virtually collapsed in the years immediately following the Panic of 1819, Mary Wingfield Scott suggests that Richmond’s eastern suburb, where land was cheap and taxes were lower than in the city, continued to see an occasional new building. At least one house, the Moore House at 612 North 27th Street, appears to have been built before 1825, while another house, the Slater House at 405 North 27th Street, was built in 1835 by local builder John F. Alvey. These were two of the few houses in Richmond constructed during those lean years. Both dwellings were built in a vernacular Federal style.

By the beginning of the 1840’s, Richmond was well on the road to economic recovery. The coming of the railroad and the related expansion of the iron industry brought new citizens to Church Hill North. As the area became more crowded, builders filled in surrounding space with more houses. A good example is the Greek Revival-siyle house at 2706 East Clay, which was built essentially in the back of the Parkinson House at 501 North 27th for Mr.Parkinson’s daughter. The attached houses at 2605 and 2607 East Leigh Street, built around 1847, are a good example of the several modest pairs of two- and three-bay dwellings designed to share a central chimney. Buildings of this sort indicate the extent to which speculative housing construction had become the norm in antebellum Church Hill North. By the late 1850s, at least one large-scale builder, Hiram Oliver, was active in the neighborhood.

Listed in various Richmond directories as the manager of T.C. Williams, a tobacco manufacturer, and the first treasurer of the neighborhood Masonic lodge, Oliver continued to build speculative houses in Church Hill North. In her book, Old Richmond Neighborhoods, Mary Wingfield Scott pays tribute to the quality of Oliver’s work in Church Hill and gives reference to his attached houses at 2813 and 2815 M Street, built in 1846. It is believed that eight of Hiram Oliver’s houses still exist in Church Hill North.

In addition to attached houses dating from the 1840s, Church Hill North has a good number of detached single-family houses that were not built as speculative properties. A number of them are all the more remarkable for the length of residency of the original owners. J. W. Ferguson, who built the frame two-story Greek Revival-style house at 500 North 26th Street in 1854, lived at this address for over thirty years. The Richardson family, who built the virtually identical Greek Revival-style houses at 618 and 620 North 27th Street in 1843 and 1847, respectively, retained ownership of the house at 618 until 1913. A. Atkinson, who built 625 North 26th Street in 1856, remained at this address until the mid-1880s. Interestingly, both Ferguson and Atkinson seemed to be conscious of the name of the neighborhood in which they lived, for they added to their addresses in the 1855 edition of Butler’s the two words “Church Hill.” At that time,their part of Church Hill was still located in Henrico County.

The taste for Greek Revival-style homes seems to have been very pervasive in northern Church Hill through the last decade before the Civil War. Mary Wingfield Scott suggests that in the suburbs east and north of the city, houses continued to be built on older models. The Susannah Walker House at 503 North 28th Street, a Greek Revival-style house built in 1860, is more suggestive in its scale and its gable roofline of the Richardson houses built in the mid-1840s. A few houses such as the Sutton House at 411 North 27th, the Reuben Ford House at 419 North 27th Street, and the Peay House at 500 North 29th Street, all exhibit shallow hipped roofs with continuous cornices on all four sides of the structure. The only other late antebellum house in northern Church Hill that was built in any style other than Greek Revival is the Italianate-style rowhouse built to resemble a villa at 521 and 523 North 29th Street. Constructed in 1860, this speculative house is among the last dwellings constructed before the Civil War. The simplicity of design of these speculative houses suggests a lack of sophistication on the part of the builder, and at least one writer implies that most of the residents of the area at this time were simple country folk.

At least one resident of the area, Reuben Ford, was progressive enough to be associated with the finest example of Greek Revival architecture in Church Hill North. He was the first rector of the nearby Leigh Street Baptist Church, which was built in 1853 at the corner of Leigh and 25th streets. Designed by Samuel Sloan of Philadelphia, this building is individually listed on the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places.

In addition to being the most remarkable structure in Church Hill, this building boasts the most extensive use of decorative ironwork in the neighborhood as well. The iron stair rail is credited to Asa Snyder, while a portion of the iron fence was moved in 1938 from the Jaquelin Taylor Row at Capitol Square to where it now stands in front of the wing that was added to the church in 1911.

On the eve of the Civil War, Church Hill was one of Richmond’s largest middle-class neighborhoods, an area which one Richmond newspaper described as combining the advantages of town and country. Church Hill North was still a part of neighboring Henrico County at that time. Although no other reference can be found to substantiate his claim, Samuel Mordecai suggests that this was not for want of trying on the part of Richmond. At this time, Church Hill North was greatly isolated from much of Richmond, a fact often overlooked today. Antebellum writers such as Mordecai describe the irregularity of Church Hill terrain, and suggest that the only dependable access to Church Hill was up to 25th Street. Mary Wingfield Scott relates that even this route was not without its hazards.

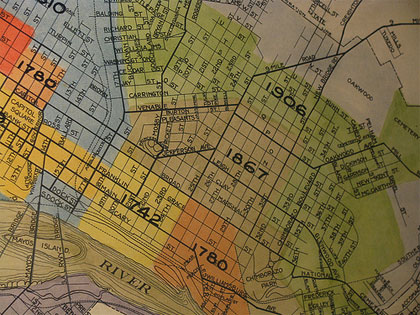

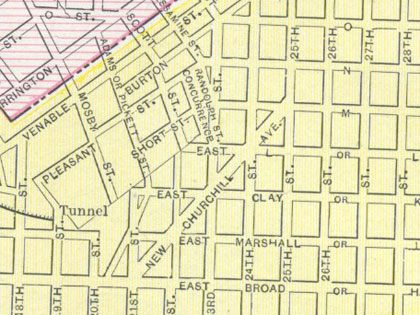

Neighboring Union Hill was not connected to Church Hill North by numerous thoroughfares as it is today, and the most cursory examination of the Michie Map of 1867 reveals that streets such as Clay and Leigh actually terminated on both sides of the neighborhood. To the north and east of Church Hill North, much of what is today the city of Richmond was uninhabited farm land. Only the neighboring portion of Church Hill to the south was more developed. Of this antebellum neighborhood, an estimated 90 structures remain today in Church Hill North. Regrettably, much is gone, including the two communities of free blacks which existed at that time. The community in the 2100 block of East Marshall Street disappeared before the end of the last century, while the second, located in the northeast corner of this neighborhood, was replaced by the t in the 1970s. It is important to note that references, such as Mary Wingfield Scott, suggest that apparently no prejudices existed at that time against a black resident living wherever he could afford to build or rent.

After the Civil War

During the Civil War, the residents of northern Church Hill North focused on needs more pressing than expansion and growth. For this reason, the Michie Map of 1867 is probably a true representation of what antebellum Church Hill resembled, as far as the numbers and location of structures might indicate. However, in his text, Richmond After the War 1865-1890, Michael B. Chesson states that Church Hill had five times as many stores in 1867 as before the war.

After the war came annexation in February 1867, Richmond’s first in over half a century, and a few years later Broad Street hill was finally paved as a second entrance into the neighborhood. With the rebuilding of Richmond came continued growth from within for established areas such as Church Hill North. A comparison of the F.W. Beers map of 1876 and the earlier Michie Map reveals a flurry of new construction during the 1870s, and Mary Wingfield Scott explains that the tendency was to fill up the big yards of the much older dwellings. Chesson suggests that annexation not only brought much needed money into the city’s coffers, but was also done to relieve the crowded housing conditions in the older sections of Richmond, many of which had been burned at the end of the Civil War.

Several new names appeared upon the scene at that time – Edwin Cannon, Armistead Neal, Lafayette Billups, E. C. Pleasants – all builders &r the war. Other names continued to remain associated with speculation in the area, such as Hiram Oliver and the Richardson family. These developers and numerous private individuals built the bulk of what can be found in Church Hill North today: an estimated 75 percent of all buildings in Church Hill North were constructed between 1862 and 1900. Most of these houses have low roof lines, bracketed eaves, floor-to-ceiling windows on the ground level, and porches embellished with turned posts, and spindle friezes.

They are abundant throughout north Church Hill North, and with a few exceptions, were built of wood, a contrast to the many brick houses that were built in neighboring St. John’s Church Historic District at that time.

Despite the depression of the mid-1870s, Richmond continued to revive as a commercial and manufacturing center, with over 7,000 employed in the burgeoning tobacco industry alone. During that time, an extensive tunnel under Church Hiil was built by the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway to connect with its port terminus at nearby Rocketts Landing. A decade later, the ravine separating Church Hill and Union Hill was filled and graded and Church Hill Avenue, now Jefferson Avenue, was constructed. Originally designed as a wide, fashionable boulevard for larger homes, the potential of this street was never realized, having been completely eclipsed by its contemporary, Monument Avenue.

Still, housing continued to be built, with row houses becoming popular in the 1880s and 1890s. In 1884 the gradual slope of East Marshall Street was developed with a row of five attached Queen Anne-Style houses located in the 2200 block. During the 1880s and 90s the last large tracts of available land were subdivided into lots for homes. In 1894 the occupants of the Adams-Picket Cemetery located in the 2300 block of East Marshall Street were disinterred and moved to a more fitting resting place in Hollywood Cemetery.

A row of nine Second Empire-style houses was built in its place. It was also during this time that the last house occupying a half city block, the home of Cornelius Lipscomb, was demolished and replaced by a row of houses in the 2800 block of East Marshall Street, also built in the Second Empire style. Also, the vacant land belonging to Mrs.F.H.Baptist and Edwin Cannon in the 3000 block of East Marshall Street gradually began filling up with rowhouses built in a similar style. Apparently, it also became popular to remodel older frame structures employing the latest styles, but actually concealing their antebellum origins.

Recently, a study of entries in the Hill was conducted on 50 houses located in the neighborhood. The houses selected were typical restored homes of varying ages and styles. The insight into late-nineteenth-century and turn-of-the-century Church Hill North was immense; all of the 50 houses were in place by 1895. While some families such as the Parkinsons, Fergusons, Moores, Richardsons, Olivers, and Atkinsons were still in the neighborhood in the 1880s, only the Richardsons, and thereafter newcomers such as W.A.O. Coles and the Billupses, were still in place by 1900. The Fergusons had become affluent enough to move to a better part of Church Hill, while the Atkinsons had moved to the city’s prestigious Gamble Hill neighborhood. Resident servants, black or otherwise, while common in the 1880s disappear from the entries by 1900. Also by 1900, the number of black residents began to decline, while at the same time ethnic surnames, such as Comoli, occasionally occur in the entries.

Interestingly, what is known about the population of Church Hill North in the 1890s confirms that six percent of the adult male population was foreign born, and 28 percent was black. The remaining adult males were white and native born.

As stated earlier, more than 90 percent of all structures existing today in Church Hill North were in place by 1900. With the exception of a few multi-unit apartment complexes built after 1950, most early- to mid-twentieth-century construction was either commercial or institutional in nature, and the bulk of it can be found on either East Marshall Street or North 25th Street. Examples include the Classical Revival-style American Bank, now Deliverance Tabernacle, at 400 North 25th Street; the Masonic Temple at 418 North 25th Street; the Art Deco-style Patrick Henry Theater at 418 North 25th Street; and the brick and stone Colonial Revival-style Billups Funeral Home at 2500 East Marshall Street. Of these buildings, only the funeral home and the Masonic Temple still serve the function for which they were originally built. Other interesting structures dating from this century include the instructional wing that was added to the Leigh Street Baptist Church in 1911, the Chimborazo Middle School in the 3000 block of East Marshall street, built in the early 1960’s, and the Asbury United Methodist Church at 324 North 29th street, constructed in 1968 to replace the original St. James Methodist Episcopal Church that was built in 1887.

Decline and Renewal in the Twentieth Century

Writers of twentieth-century Richmond describe this period as one of decline for Church Hill. The antebellum neighborhood, which 50 years earlier had been described as middle class, was electing citizens of humbler station to public office at the turn of the century. The study of the Hill reveals that many of the larger houses in Church Hill North had been subdivided into apartments by 1930. By 1950, the time of the publication of Mary Wingfield Scott’s book, Old Richmond Neighborhoods, the author refers to Church Hill as having “sunk to near slum condition.” Church Hill, having been so close to the center of Richmond, suffered when Richmond’s center moved west. Perhaps, it was this shifting of interest that also saved Church Hill from massive demolition and reconstruction in the twentieth century.

Just as the history of Church Hill North did not end at the turn of the century when growth had reached its peak, it also did not end in the 1950s. In the 1960s and 1970s, urban renewal introduced the concept of demolition and infill housing that removed all traces of most of neighboring Shed Town, including the houses of free blacks that had existed there as early as the 1830s. At that time, the population began leaving Church Hill North as well. The associated census tract dropped from 4,613 in 1960 to 1,996 by 1980. In the 1980s an attempt to stabilize the neighborhood was undertaken by Historic Richmond Foundation. That organization, which had been so successful in launching a restoration pilot block in the St. John’s Church Historic District, purchased more than 30 houses in Church Hill North with the intention of reselling them for restoration to resident home owners.

In order to inspire proper restoration, the deed to each house came with design controls governing the restoration of the structure. as well as mutual covenants binding both the owner and the Historic Richmond Foundation to support the creation of historic districts in the area on the state, federal and local levels. Due to Historic Richmond Foundation‘s initial activity, more than 200 properties have been restored in Church Hill North since 1983, mostly by white and black first-time homeowners who have decided to look to the past in making their homes.

The Church Hill North Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in September of 1997. The original listing covered the area between Marshall and M Streets, and 21st and 30th Streets. In 2000, the district was extended north to include areas up to T Street (PDF). In 2007, the Church Hill North City Old & Historic District was created.

Credit and Sources

The text above is almost entirely sourced from the the registration form from the Church Hill North application to the National Register of Historic Places (PDF). The original document, dated 1996, was put together by David Collett and Isabel M. Smith and includes much more more than is shown here. Check out the original form to learn more about the Church Hill North Historic District, or read up on any of the other sites in Richmond that are listed on the National Register.

The map at the top is a detail from the city’s Richmond Districts and Sites on the National Register (PDF). The 2nd map is a detail from the city’s City Old & Historic Districts in Richmond, Virginia (PDF). Other embedded maps link to their sources.

The black & white photo at the top is from the Church Hill North registration form. All other photos are by John Murden.

cool post… thanks as always for all the information you make available to all!

This is damn cool. I moved to the 600 block of N. 27th a little over a year ago, and I’ve wondered about the history of some of the houses on our block.

The city’s tax records say my house (I rent, so it’s not *mine*, but you get the idea) was built in 1906; it’s identical to three others (and it looks like there was a fourth that’s now an empty lot), so I assume it was part of the building boom in the late 19th and early 20th century.

However, the city’s information is greatly flawed. Like the house at 1614 N. 21st St they have being built in 1915 and that house was built about 100 years earlier. A lot of houses they guessed the year they were built… just like the misinformation in neighborhood locations and names.

John thanks again. I did see a sentence where I think a word is missing.

Re: Cadeho, I heard from an engineer who does historic renovations in Jackson Ward that the City’s tax building burned down around 1913, so you’ll find a lot of extremely old houses that say they were built around that time, simply because the City no longer had the records and just started over! I’d bet that was the case at 1614 N. 21st

Just found this article and wanted to post a link to the Historic Registry:

http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Cities/register_Richmond.htm

Also for the St. John’s area listing:

http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Cities/Richmond/127-0192_St._John's_Church_HD_1991_Final_Nomination_Amendment.pdf

I was born and raised in Church hill in 1965,first i lived in a house that was directly next door to the light foot funeral home and on 27Th st.And the last place was at 509 N 29Th street. I found history on my own by playing in the woods and parks i even found a partial tunnel.And yes Church hill was going down as in value but i don’t know about the slum stage yet but it was getting ruff. I was last there in 2010 and i see that Richmond is cleaning that place up and i wish i had known what i know now a long time ago i would have bought my childhood home.

And one more thing i forgot to disclose, the house that i last lived in which is 509 N 29Th street was Haunted yes i said Haunted. True story, i would love to share my stories.

yes i live in Church part of my life i love Church Hill went to 2 school live over a groc Store at 17th and Broad St me and my family oh the store was Ray’s market i live in Church Hill

back in the 1942-43-44- 45-thur 50’s

Ethel Bailey Furman personal home 3025 Q St his for sale build with carved stone build like museum build to last for ever if interested email realtor58379@gmail.com

Hello! I Shonda Renee Gillum

I feel that if the rehab project wants to convert it would be a blessing for everyone to keep things the same by the building

being so old and of vaule that’s why the building is called the church hill historic none by introdutions of the early history and it was developed in the nineteenth century it would be best to rebuild to keep the history going for his family and for the people of old ages for us it is amazing to see something so old thanks for your understanding and ,unity My the father & son be with you all on this one

Robert w. Williams my grandfather had funeral home located 3019 P Street /3024 P Street in the 1900’s-1935. His home was located 911 N.32nd Street. Does anyone know about the funeral home.