RECENT COMMENTS

Escape from Libby Prison

This year marks the 150th anniversary of one of the most remarkable prison breakouts in American history.

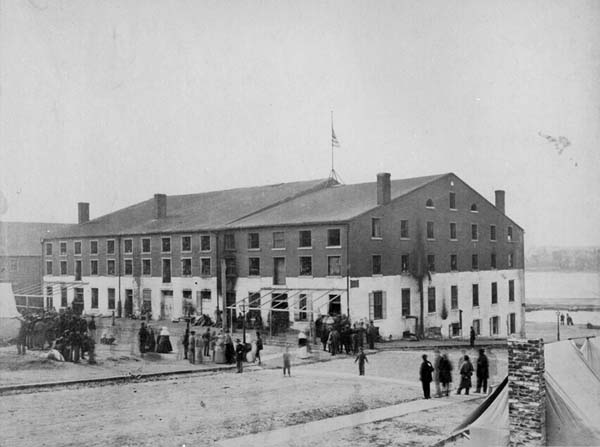

On the south side of East Cary Street, across from the Virginia Holocaust Museum, once stood Libby Prison, a vast brick tobacco warehouse that became one of the most notorious Civil War prisons in the South.

Built in the late 1840s by John Enders, who was killed during its construction, the structure actually consisted of three separate pieces built to form one warehouse. In 1861, the warehouse was purchased by Maine native and Church Hill resident Luther Libby, who used it to house his ship chandler and grocery shop. A year later, the Confederate government seized the building to use as a prison for captured Union soldiers, calling it Libby Prison. Shortly after, it was dedicated to house only Union officers, with some African-American Union soldiers.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

Conditions in the prison were miserably uncomfortable and unhygienic. The windows contained no glass, and in winter, cold wind and rain blew directly on the men, who were denied blankets and cots and slept on the bare floors. In summer, the heat inside the building was unbearable.

The men endured tiny portions of rotten, insect infested food. Their bodies crawled with lice. Given its proximity to the river, the building also had a severe rat infestation, centered in a portion of the basement the soldiers nicknamed “Rat Hell.”

In 1862, the North and the South had worked out a prisoner exchange which allowed for equal exchange of men captured in battle. After President Lincoln issued a call for black men to join the Union Army, however, the Confederate President Jefferson David said that no African-American soldiers captured in battle would be exchanged. Lincoln then suspended exchanges until the Confederacy agreed to exchange black Union soldiers. As a result, the population in war prisons everywhere swelled; Libby Prison’s population reached 1,200.

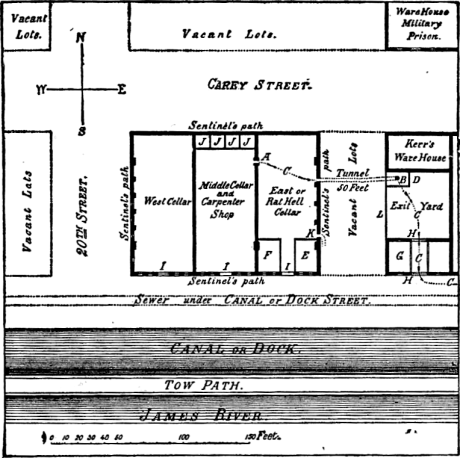

Col. Thomas Ellwood Rose, taken prisoner at Chickamauga and housed at Libby Prison, had enough of these conditions and was determined to escape. While examining Rat Hell as a possible escape point, he met Major A.G. Hamilton, in the room for the same reason.

Working overnight for twelve days, Rose and Hamilton tunneled through to a sealed-off room by chiseling through a fireplace and digging a route through the wall. They hid the dirt dug out of the tunnel under a thick layer of straw strewn on the floor in Rat Hell. At 4:00 every morning, they slipped back through the fireplace, replaced the bricks and mortar, and lay down with the other sleeping men.

Rose and Hamilton enlisted the help of a dozen other prisoners, with the men digging in shifts while others fanned air into the hole and kept lookout. They worked in complete darkness, rats swarming their arms, legs and faces. The first three attempts failed.

Seventeen days after starting the fourth tunnel, Rose broke through directly under a shed outside the prison’s fence. From there, escapees could simply walk through a gate to Dock Street and disappear into the night.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

On February 9, 1864, Rose, Hamilton and 107 other Union officers slipped through the fireplace into Rat Hell and entered the tunnel, one at a time. Each man crawled through the pitch black tunnel to the tobacco shed, walked out the gate and slipped into the shadows of Dock Street – right under the noses of the Confederate sentry.

The fireplace bricks were replaced by men who chose not to escape. The men were so quiet that escape was not discovered until roll call the next morning, by which time, some of the men had been gone for twelve hours. It was several more days until the sentry discovered the tunnel.

Although two men drowned after escaping, and roughly half of the men were recaptured – including Colonel Rose – the rest made it to Union lines in Williamsburg. It was the biggest prison escape of either side during the Civil War, and one of the most successful in American history.

— ∮∮∮ —

Wonderful piece, Tricia!

Interesting!

In my September CHA article about spy and Richmond Underground leader Elizabeth Van Lew of Church Hill, I mentioned that her information smuggled out of Richmond that revealed the weakness of the Richmond defenses in early 1864, resulted in the unsuccessful Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid on Richmond to free Union prisoners. And she is possibly responsible for the 109 prisoners who tunneled out of Libby Prison, then slipped across enemy lines.

The structure dismantled and moved to Chicago in 1889 to serve as a war museum. It was dismantled again in 1899 after the façade was incorporated into a new stadium, with its pieces sold as souvenirs.

There were a few who made it all the way to Zihuatanejo.