RECENT COMMENTS

The Manchester Industrial Historic District

One of my ongoing projects has been to try to bring to life the National Register of Historic Places applications for different neighborhoods around the city. These are great resources that have been researched and documented by actual trained historians for tons of sites across the state.

While this is slightly outside of the typical footprint for CHPN, we present today a history of the Manchester Industrial Historic District in the same format, put together by the good folks at Rocket Werks.

— ∮∮∮ —

THE MANCHESTER INDUSTRIAL HISTORIC DISTRICT

- Early Days

- Incorporation

- Civil War

- Annexation & Afterward

- Growth of Industry

- Maps

- Credit and Sources

- More Neighborhood Profiles

— ∮∮∮ —

EARLY DAYS

The Manchester Industrial Historic District lies geographically at a site naturally suited to industry. Serving as a central point for communication and trade, the area of the falls of the James River was inhabited by Native Americans for more than 1400 years before English settlers arrived.

In 1607, Captains Christopher Newport and John Smith and a company of twenty-three men navigated the James River to the falls and claimed the area for King James I of England. The explorers planted a wooden cross at their landing at the falls on what was then a small island near the north end of the present Mayo Bridge.

Recognizing the region’s commercial potential, the first permanent settlers arrived in 1609 and prospered, though not without adversity. In response to Indian raids, Fort Charles was constructed at the falls of the James in 1644. The fort marked the beginning of continuous settlement in the area of the Manchester Industrial Historic District. Following the establishment of cloth and gristmills, the area was named “the Mills”.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

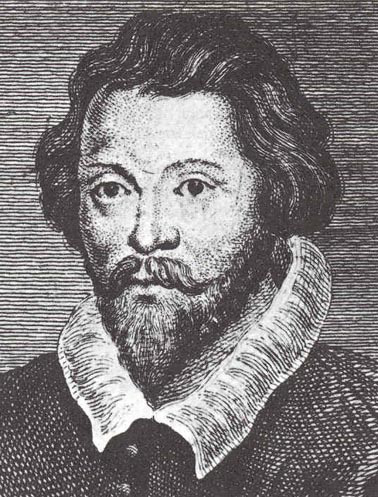

In 1676, William Byrd I inherited tracts of land on both sides of the James River. William Byrd I was successful as a planter, tobacco producer, and trader of a variety of manufactured goods. He also increased his wealth by storing tobacco at his warehouse at the falls.

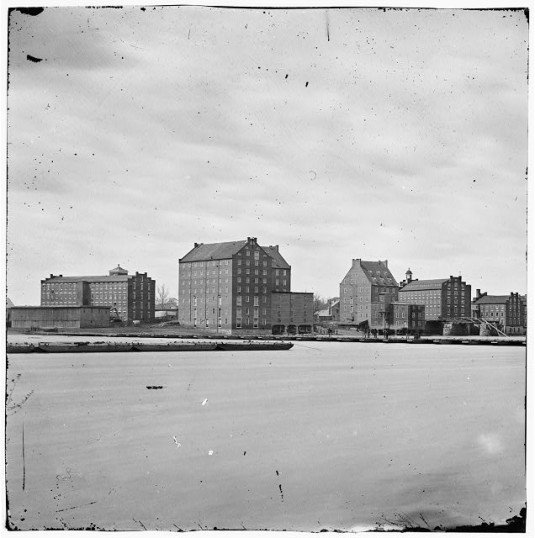

Byrd’s Mills, mentioned in diary entry in 1732, were the oldest in the nation in continuous operation between 1732 and 1852. Located on the south end of the Mayo Bridge, the mills were purchased from William Byrd II by William Mayo who also acquired the canal that powered them and extensive water rights in the James River. Mayo’s Mills were then purchased by the firm of Dunlop, Moncure, & Co. in 1852.

A new mill plant, the Dunlop Mill, was completed in 1853. One of only two flour manufacturers in Richmond at the turn of the century, Dunlop Mills continued to operate until 1932.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

INCORPORATION

Manchester was incorporated in 1769. Early in 1767 William Byrd Ill was advertising town lots for sale there. Between August of 1767 and October of 1768 Byrd offered his holdings in a huge lottery and so disposed of many of his properties.

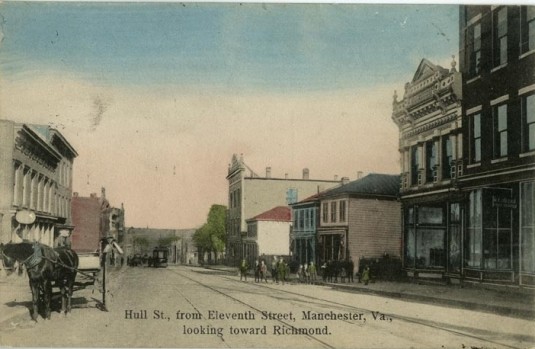

Following the plan and survey made by Benjamin Watkins the town included 312 lots and several tenements close to the James River. The Manchester street grid included the following streets running east to west: Decatur, Hull, Bainbridge, Porter and Perry. Named for American Naval heroes, the name and placement of the streets remain the same today. Streets running north to south, shown on an 1835 map with their original names (Ludlow, Wadsworth, Summers, Jackson, Briddle, Barney, Allen, Burrows, and Warrington, were later changed to numbered streets, First through Ninth. Eighth Street is now called Commerce Road.

Early maps for Manchester show large swaths of land with names like Buchanan’s Pasture and Lyle’s Pasture that are not part of the grid. These private holdings were gradually absorbed into the street grid system.

Between 1730 and 1788, Coutt’s Ferry provided the only public transportation across the river between Manchester and Rocketts in Richmond. The ferry site is located approximately 850 yards down river from the south end of the current Mayo Bridge.

The riverfront area between the inlet and outlet of the Manchester Canal is known as the Manchester Commons. John Mayo claimed to have inherited this open land by the river from his father, who had apparently purchased the land from William Byrd I. Officials of the Town of Manchester held that the land belonged to the citizens of the town in order to secure public access to the river.

Because Mayo apparently did not possess a properly executed deed, rightful claim on the land was resolved in 1811 in a court case known as Mayo vs. Murchie. Mayo was forced to relinquish the land to the town of Manchester. A large grassy stretch of land that was known as the Manchester Commons is visible today along the riverbank east of the Mayo Bridge. The City of Richmond acquired the property when Manchester was annexed to the city in 1910.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

Although few buildings were constructed in the Richmond environs during an economic depression that lasted from 1826-1840, economic recovery began when railroads were constructed between Manchester Wharf and Midlothian farther south in Chesterfield County in the early 1830s and between Richmond and Petersburg about 1838. Tracks were extended from Manchester to Danville in 1847, and a railroad bridge was built across the James River in 1850. The railroad helped to make Manchester one of the most important commercial and industrial centers in Virginia.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

Before the Civil War, most of the flour manufactured in Richmond was shipped to Brazil in exchange for coffee. In fact, Richmond was the nation’s number one ranking coffee port. As evidenced by listing in the Richmond directories for the period between 1888 and 1910, numerous coffee-related industries were located in Manchester after the war including the Cheek-Neal Coffee Company that specialized in coffee grinding and packing. The structure at 201 Hull Street is a distinctive five-story concrete and brick Commercial style building built in 1920 as a manufacturing warehouse structure for the Cheek-Neal Coffee Company. The building has three structural bays with six-over-sixteen light metal windows on the first floor and large steel, multiple-light sash windows on the second through fifth floors. It also features a projecting precast concrete cornice with geometric pendants topping each of four raised pilasters across the front facade.

— ∮∮∮ —

CIVIL WAR

During the Civil War the Confederate Navy Yard was located on both sides of the James River-at Rocketts on the north side and adjacent to Manchester on the south side. Several artillery batteries were also located in Manchester. Although the industrial capabilities of Manchester were committed to the Confederate cause from 1861 through 1865, manufacturing suffered because the hostilities halted the flow of raw materials to factories.

— ∮∮∮ —

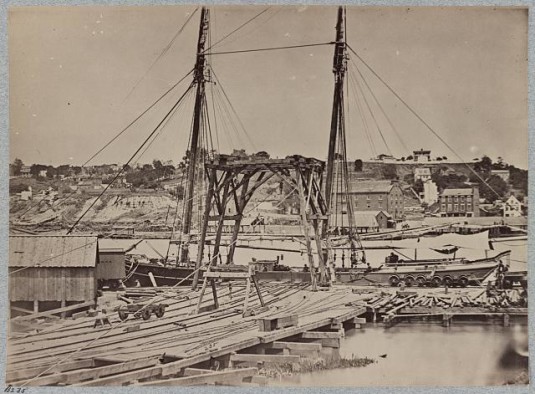

Confederate Navy Yard via Library of Congress. View on the dock on south side of James River opposite Rocketts, Richmond, Va., April, 1865

— ∮∮∮ —

In addition, military occupation disrupted sales and, in some cases, stopped production altogether. After the Civil War, Manchester suffered widespread depression along with other towns in Virginia. Citizens endured poverty, muddy streets, and a lack of municipal services. The 1870s were economically difficult years, and many mill owners suspended manufacturing or sold their businesses in the face of declining or nonexistent profits. The depression of the 1870’s spurred economic leaders to call for a “New Southern with greater investment in manufacturing to create a diverse, well-balanced economy of agriculture and factories. Development advocates urged southern investors to compete against northern industrialists. The success of Manchester’s industries in the 1880s is not surprising given the region’s industrial resources. The easy availability of natural resources including tobacco, cotton and coal, river access to ocean ports, and a growing population that provided labor and a market for manufactured goods spurred development.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

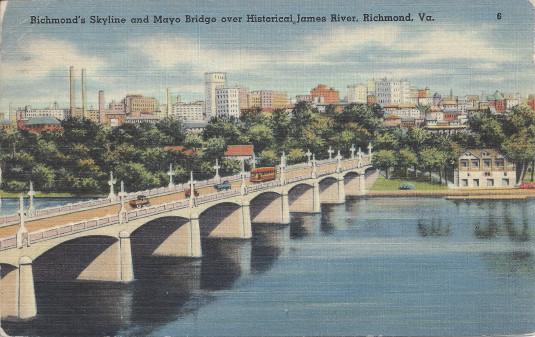

The site of the current Mayo (Fourteenth Street) Bridge has been continuously occupied by a bridge since John Mayo was granted a charter to build the first bridge to connect the north and south banks of the James River in 1785. Mayo’s son, John Mayo, Jr., received authorization from the General Assembly to continue his father’s work. A wooden bridge was constructed in 1788. Successive replacements were built as the bridge was repeatedly washed away during periods of flooding or otherwise destroyed as in 1865 when Confederate forces retreating from Richmond burned the bridge.

— ∮∮∮ —

GROWTH OF INDUSTRY

Manchester served as the county seat for Chesterfield County for five years between 1871 and 1876. Having grown in area and population, it became an independent city in 1874. Railroads, shipping, mining, and manufacturing stimulated population growth and commerce. In the late 1870s the growth of a wide spectrum of small industries helped to compensate for the general decline in the flour and iron industries. The thriving tobacco industry got a boost from the development of new technology and an abundant supply of high quality raw material.” Mass production of cigarettes increased the need for packaging, box design, chemicals, and dyes. Both Richmond and Manchester saw a surge in paper production.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

Paper making had been an important industry in Manchester since 1834 when Franklin Manufacturing Company became the city’s first paper manufacturer. The company later became part of the Richmond Paper Manufacturing Company that had a mill operating near the Confederate Arsenal in 1874. The Manchest94 Board and Paper Company built a mill in 1863 with a 66 cylinder machine to make manila tissue. In 1890, fire destroyed the company’s facility. When the company rebuilt in 1891, the operation was converted to box board. Reorganized in 1912 as the Manchester Board and Paper Company, the manufacturer subsequently merged with the Federal Paper Board Company to become the second largest paper board company in the United States. Other paper manufacturers in Manchester during the period of significance include the Cauthorne Paper Company, the A. K. Kratz Folding Boxes Company, and the Virginia Folding Box Company. The Richmond Paperboard Company and Federal Paper Board Company, among others, operate in Manchester today.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

In 1856, Manchester had two cotton mills, two large flour mills, a foundry, several tobacco factories, and the legal rights to one-half of the water power of the James River. The most prominent of the Manchester Mills was the Manchester Cotton and Wool Manufacturing Company, constructed between 1837 and 1840 along the canal at the south end of the Mayo Bridge. The Manchester Cotton and Wool Manufacturing Company was among the first of the textile mills to operate in Manchester and was the first to use the water power developed by the Manchester Canal which later supplied power for other industries located at the falls. Although the oldest portion of the Manchester Cotton and Wool Manufacturing Company was demolished when the James River Flood Wall was constructed in 1990, portions of the west addition (1901) at 7 Hull Street, its stone foundation, sections of the water delivery system and the wheel housing are visible from the overlook at the entrance of the Flood Wall River Walk.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

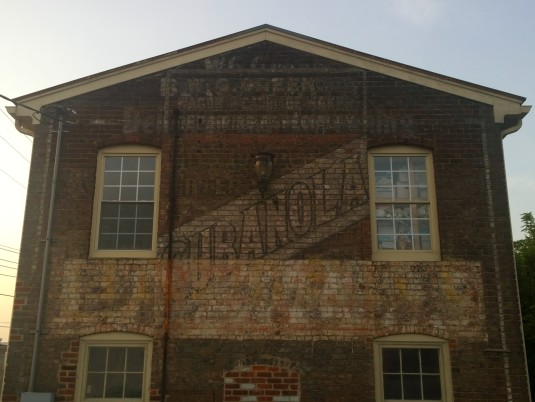

According to a publication of the Richmond Chamber of Commerce, the established industries of Manchester in 1893 included cotton mills, a paper mill, flour mills, nail mills, tanneries, sumac and bone mills, oil works, brick yards, tile works, a mattress factory, tobacco factories, fertilizing works, a furniture factory, millwright shops, granite yards, and ice manufactory. Surviving from this period is 18 West Seventh Street, the oldest building in the district, built in 1880 for the William G. Green Carriage & Wagon Makers. The structure is a two-story brick building in seven-course American bond with hipped roof, simple wood cornice, segmental arches and six-over-six wood, double-hung sash windows. The carriage door entrance has been filled in with brick. Its original attached outhouse remains intact. A faint but legible shadow of the Green Carriage & Wagon Maker advertisement is visible on the west elevation facade. The business evidently enjoyed a relatively long-lived prosperity; representative advertisements are found in the 1888, 1900, and 1910 Richmond directories.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

During the 1890s, the population of Manchester grew by one hundred percent as streets were laid off and paved, and electric lights and telephone service were secured. Two railroad systems passed through Manchester, the Atlantic Coast Line and the Richmond and Danville System. Two and factories were numerous new manufacturing facilities including the Manchester Paper and Twine Company, Southern Fertilizer Works, Robert G.Wood Coal & Wood Co., United Cotton Mills, Aragon Coffee Roasters, Manchester Transparent Ice Works, and the Richmond Standard Steel Spike and Iron Company.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

Into the 1890s significant economic diversity could be found in Manchester. Small manufacturers produced agricultural implements, paper boxes, boots and leather, bricks, brooms, twine, fertilizer, furniture, ice, mattresses, and tin ware. Advertisements in the Manchester directories between 1890 and 1910 included, among others, the Manchester Paper and Twine Company, Stephen Putney & Company Wholesale Shoe Dealers, Southern Fertilizer Works, Robert G. Wood Coal & Wood Co., United Cotton Mills, Aragon Coffee Roasters, Manchester Transparent Ice Works, the Richmond Standard Steel Spike and Iron Company, Woodward & Son Lumber Company, Allegheny Tobacco Warehouse, and the Old Dominion Distilling Company.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

At the turn of the century, local newspapers heralded the industrial success of the Richmond area. A series of industrial “trade parades” were held to celebrate the region’s commercial and industrial growth. The nature of the work force changed in Manchester as factories expanded. Black men, white women and children entered the work force. In factories, a hierarchy of labor developed with workers separated by race, gender, and wage scale. The expansion of the industrial working class precipitated efforts to unionize in order to negotiate wages and working conditions. Frustration with working conditions fostered strikes by the working class in both Richmond and Manchester. In 1903, the Street Railway strike became violent, precipitating swift and successful retaliation by the Virginia State Militia. Further strikes were quelled for more than two decades. The period of race and class conflict that began during Reconstruction and ended with white political victory gave way to an extended period up to World War I of sustained growth but little significant change in the social order.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

In the early part of the twentieth century a steady stream of laborers came to the area from rural Virginia. They came to work in the factories and in the homes of the growing, prosperous managerial and entrepreneurial class. Racial segregation was established by law, severely reducing the political and economic control freedmen had experienced during Reconstruction. White workers could anticipate upward mobility that came with good employment and the acquisition of property.

— ∮∮∮ —

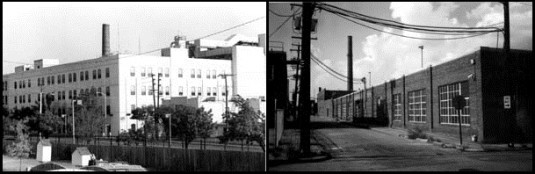

Railroads via Valentine Museum – Black and white photograph of the exterior of the Standard Paper Manufacturing Company and Southern Railway Depot on East 1st and Hull Streets. (Stead Studio, 1925)

— ∮∮∮ —

RAILROADS

The Manchester terminal of the Richmond & Petersburg Electric Railway was constructed in 1910 on Seventh Street between Perry and Porter Streets. The two-story building occupied half a city block and housed seven tracks, along with shops, offices, storerooms and waiting rooms. Small businesses developed near the terminal to provide housing and services for railway employees and passengers.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

The Southern Railroad, organized in 1894, was the third railway system in Richmond. The railway was formed from the consolidation of the Richmond and Danville and the Richmond, York River, and Chesapeake railroads. The elegant Queen Anne style Southern Railroad Depot located at 102 Hull Street was built about 1919. The one-story depot has fine Flemish bond brickwork with glazed headers and with quoins at the corners and a splayed tile roof supported by decorative brackets. Architectural details include corbeled chimneys, three-course brick arches over windows, stone sills and. unusual sixteen-over-two wood double-hung sash windows. The primary north elevation has symmetrical entrance doors separated by the original ticket window. After the depot closed, ownership was transferred to the Old Dominion Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society. The Society is in the process of developing the depot as its museum.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

Bv 1900 Richmond’s railroads were growing and facilitating continued industrial expansion. In 1899 John Skelton Williams, with the aid of Baltimore capitalists, organized the Seaboard Air Line Railroad by taking over the Richmond, Petersburg and Carolina Railroad Company. The former Seaboard Air Line Railroad Freight Depot, built in 1910, is located at 604 Hull Sired. The one-story, brick structure features a steep gable roof, corbeled chimneys and raised pilasters at each comer. The original one-over-one wood double-hung sash windows and four loading docks with wood doors survive. The former depot is now occupied by Hull Street Sod Station.

— ∮∮∮ —

ANNEXATION & AFTERWARDS

On April 15, 1910, Manchester was annexed to the City of Richmond, becoming the city’s Washington Ward. Influential members of the Richmond city government had urged annexation of adjacent municipalities in order to increase overall prosperity of the area. The annexations that took place in 1906, 1910, and 1914 quadrupled the size of the city, increasing urban investment and the extension of city services. With annexation, the quality of life in Manchester improved through the construction of new schools and the installation of new arc streetlights and sewers. An important benefit for existing businesses was the exemption from Richmond’s law against the storage of dangerous materials and the assumption by the City of Richmond of Manchester’s bonded indebtedness. In 1913 Manchester and Richmond were joined in a new way-both physically and symbolically-when the old Mayo Bridge was replaced by a new concrete span bearing the historic name.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

Construction of the current Mayo Bridge was begun in 1910, and it was opened to the public in 1913. The bridge was designed by Concrete Steel Engineering Company of New York and built by I. J. Smith & Company of Richmond. Charles Bolling, City Engineer, and G. M. Bowers, engineer-in charge, supervised the construction of the bridge. The bridge, a fine example of Beaux Arts Classicism, is built in two segments, divided by a section of roadway on Mayo’s Island. The segment to the north has seven arches, and the segment to the south has eleven arches. Each arch has a clear span of 71 feet and a rise of seven feet, 27 inches from the soffit of the arch to high tide. The piers, abutments, and arches are made of reinforced concrete. Spandrel walls are cast-in-place concrete, 3 112 feet above the bridge floor with an ornamental design of newel posts, recessed panels, and a handrail. Span sections meet at a vertical V-groove between the arch faces. An ornamental pedestal is cast in the parapet above each pier and topped with a light pole. Construction of the Mayo Bridge required 30,000 barrels of Portland cement and 25,000 tons of gravel. A total volume of 23,500 cubic yards of concrete and 400 tons of reinforcing steel was used in the construction of the bridge.

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

World War I brought new levels of prosperity to Manchester, increasing growth and industrialization. When factory workers left their jobs to join the war effort, white women took over their jobs. After the war, men returned to reclaim their previous employment. Manufacturing companies continued to adopt new technology that increased mechanization and changed the nature of the work. The wide array of small industries common in Manchester began to disappear and were replaced by larger consolidated manufacturing corporations such as the Crawford Manufacturing Company, the W. P. Ballard Company, the Federal Paper Board Company, and Reynolds Metals Company. [VDHR]

— ∮∮∮ —

— ∮∮∮ —

Today, the Manchester Industrial Historic District is changing rapidly from the manufacturing center it used to be. Everywhere you see evidence of the change as former factories are repurposed, from art galleries like Plant Zero, to the plethora of new living spaces, to upstart young businesses like Blue Bee Cider. What used to be rough and run-down is in full-bore revitalization on steroids — another urban bedroom in close proximity to downtown. The face of Old Manchester is fading, but enough remains to appreciate the industrial lifeblood it used to have.

— ∮∮∮ —

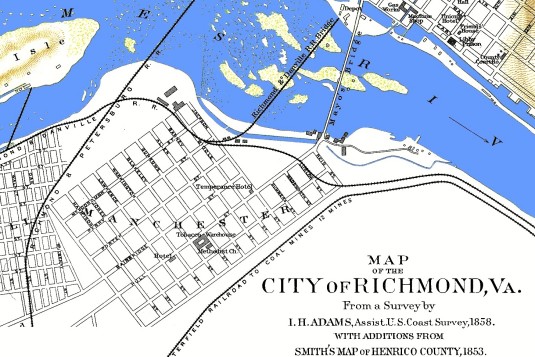

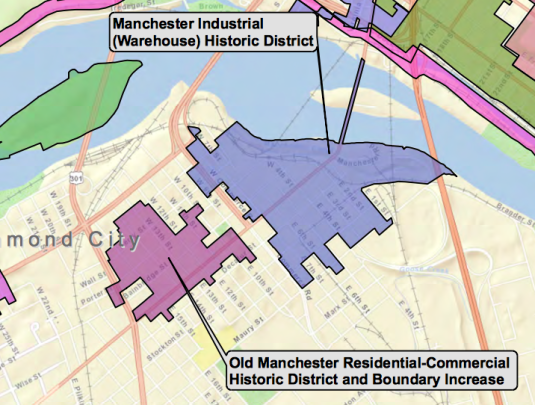

MAPS

— ∮∮∮ —

Early Manchester from Map of Richmond from the Official Records Atlas, Plate LXXXIX, #2. Prepared in 1864 by A. D. Bache for the U. S. Coast Survey (via Civil War Richmond)

— ∮∮∮ —

CREDIT AND SOURCES

The text above is almost entirely sourced from the the registration form from the Manchester Industrial Histric District application to the National Register of Historic Places. That text, dated June 2000, includes much more more than is shown here, including an entry for every property in the district.

We have simply made some edits to the text, formatted it to HTML, and added the embedded media. The bulk of this was done by the good folks at Rocket Werks, with some minor assistance by John Murden.

Photos via Rocket Werks unless otherwise specified.

— ∮∮∮ —

NEIGHBORHOOD PROFILES

Complete list of neighborhood profiles in the series:

- The Union Hill Historic District

- The Oakwood-Chimborazo Historic District

- The Fairmount Historic District

- The Church Hill North Historic District

- Photographs of old Fulton

- Public housing in Richmond

- The Highland Park Plaza Historic District

- The Chestnut Hill/Plateau Historic District

- The Brookland Park Historic District

- The Town of Barton Heights

- The Ginter Park Historic District

- The Fan Area Historic District

- The Fan Area Historic District Extension

- The Boulevard Historic District

- The Manchester Industrial Historic District

Great historic piece on Manchester!