RECENT COMMENTS

Babies born within 5 miles of downtown RVA face 20-year difference in life expectancy

A minimally-edited press release from VCU:

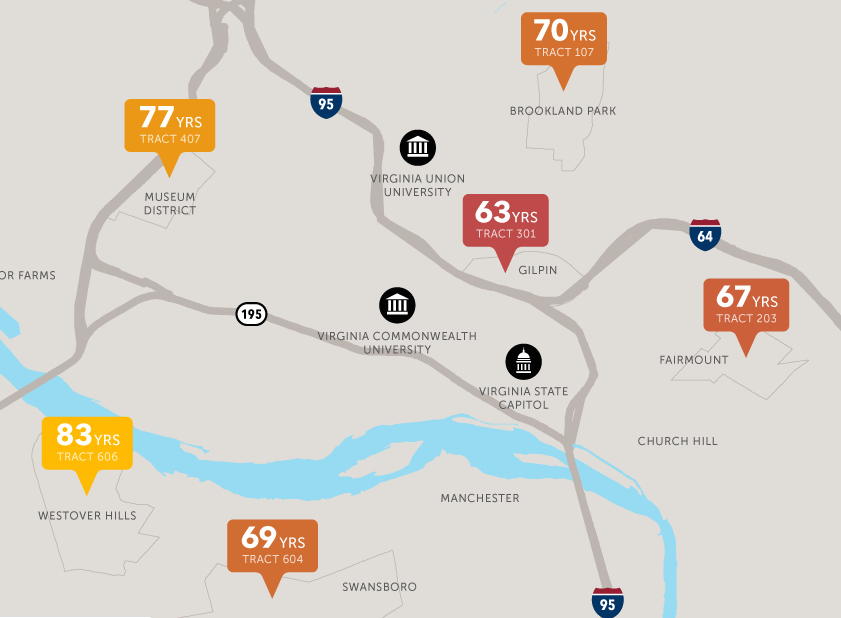

A new life expectancy map released today illustrates that opportunities to lead a long and healthy life can vary dramatically in Richmond based on where you live.

For example, life expectancy differs by 20 years in the 5.5 miles it takes to drive between Westover Hills and Gilpin and by 16 years in the few miles that separate Westover Hills and Fairmount.

Researchers at the Virginia Commonwealth University Center on Society and Health, with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, created the map using census tract data from the Virginia Department of Health.

The map is the latest in a series developed to raise public awareness of the many factors that shape health, particularly social and economic factors. The dramatic health gaps the map demonstrates can be used as a conversation starter to support the work of local officials and community organizations looking to address these factors in order to improve, maintain and reclaim their community’s health. These differences between neighborhoods rarely are due to a single cause. A growing body of research shows that health is influenced by a complex web of factors. These factors include opportunities for education and jobs; safe and affordable housing; availability of nutritious food and places for physical activity; clean air; and access to health care, child care and social services.

“The health differences shown in these maps aren’t unique to one area. We see them in big cities, small towns and rural areas across America,” said Derek Chapman, Ph.D., associate director for research, VCU Center on Society and Health. “Our goal is to help local officials, residents and others understand that there’s more to health than health care and that improving health requires having a broad range of players at the table.”

For example, a VCU-led initiative aims to reduce health disparities in Richmond through a partnership involving the VCU Health System Virginia Coordinated Care program for the uninsured, the VCU Office of Health Innovation, Richmond City Health District and the Institute for Public Health Innovation. The project will deploy community health workers to address social factors and help residents obtain better care in lower cost community-based health care settings rather than relying on more costly visits to emergency departments.

Additionally, the 7th District Health and Wellness Initiative is a collaborative effort to improve community health and wellness through health education and outreach; health promotion; and screening, treatment, and medical homes that coordinate patient care. The initiative has been in place since 2009 and involves partners in the Richmond City Health District, VCU, Bon Secours, Sports Backers, the Minority Health Consortium, and others. Its success in promoting health has prompted the recent expansion of the program into the north side of Richmond.

“To build a culture of health we must build a society where everyone, no matter who they are or where they live, has the opportunity to lead a fulfilling, productive and healthy life,” said RWJF President and CEO Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, M.D. “There’s no one-size-fits-all solution. Each community must chart its own course and everyone has a role to play for better health in their homes, in their neighborhoods, in their schools and in their towns.”

VCU and RWJF released a map of Las Vegas in March 2015 and of the District of Columbia; New Orleans; Kansas City, Missouri; Minneapolis; and the San Joaquin Valley in California in 2013. Maps of Chicago, New York and Atlanta are being released concurrently with the Richmond map. See societyhealth.vcu.edu/maps. In the coming months, 15 more maps will be released for cities and rural areas across the country. Follow the discussion on Twitter at #CloseHealthGaps.

TAGGED: map

And I’m totally fine with that because I love being here.

The methodology on this is pretty suspect. They’re using a method that is commonly used for national level life expectancies but when it’s used at a regional level like this it breaks down. This completely ignores mobility.

If an area is a place where most of the residents moved there when they were older does that really translate into a longer life expectancy for births? Or take the projects where most of the residents are younger. The only people dying there are younger people because those who get out live longer.

To me it looks like someone had a narrative they wanted to tell so they didn’t consider these limitations. I’m not quite sure what their calculations produce but it’s not a life expectancy for a new birth. Maybe the average age that someone living in that neighborhood right now will die at (which isn’t all that useful to know)?

Students form VCU Nursing school have been great in leading healthy living programs at our Boys & Girls Club in Church Hill.

I see something else with this map. It shows demographic differences around the city. That lower income, majority black neighborhood concentrations have a lower life expectancy because of poor eating habits (pork, salt, sweets, junk food, etc..) versus suburbs where income is higher and eating more healthy because they can afford to do so.

I passed along a link to John the other day from an online business site that uses demographic charts for zip codes and for our own 23223, it shows a population of nearly 48,000 people, 53% female, and 81% black. I am not sure how accurate it is but suspect they are using census data?

Alex- 100% agree. From an experimental standpoint this seems (from the surface) totally messed up. You’re making assumptions about neighborhoods NOW that have changed drastically over the past 60-75 years. It means almost nothing. Then on top of that you’re using the location of where people live and saying that somehow that could affect their life expectancy. Does it make sense intuitively? I guess so, but there’s absolutely no way you could control for everything possible to determine the causes.

I would advise anyone reading this not take it at face value at ALL. I’m sure the researchers mean well and maybe even used best practices, but their conclusions cannot be possible. And honestly, this headline (probably taken from the report itself) is misleading and incorrect. There’s no way to know whether a birthplace affects these things.

I’m guessing that the researchers know a little more about this than you guys do. BUT YOUR INTERNET OPINION IS VALID.

DA, there’s plenty of shit research that gets published. If you’d like to explain where you think I missed the mark I’d be glad to discuss with you.

This would need to be a 80+ year study if it were actually tracking the lives of babies born in certain neighborhoods. The title should probably read: “Life Expectancy Based On Terminal Address.”

This is important because there are many factors that are set in motion the day a child is born and this may guide but does not determine destiny. Still, I think we all share concern when we consider that there is a portion of our neighborhood (through a number of factors) has 20 years shaved off their lives.

Michael, the methodology can be found at the link. The Chiang methodology they used is a fairly standard approach for calculating national level life expectancies. There’s serious gaps when you use it too granularly like this because you don’t have a static population.

I also agree with most of the assessments made but was merely objecting to the attempt to give it more weight with a sloppy analysis. There’s other ways to prove those points that don’t require torturing data.

Does this take into account the babies who were born again?

Healthy communities a matter of life or death

http://www.richmond.com/local/michael-paul-williams/article_c5c14d95-1cf6-5be3-86ec-6943f30e1f78.html

Richmond’s great divide

http://wric.com/2015/11/11/richmonds-great-divide/